Introduction.

Taranto is a city of striking contrasts: ancient and modern, mythic and industrial, noble and defiant. Founded by Greek colonists and named after the mythical Taras, son of Poseidon, it occupies a strategic position along the Ionian coast of southern Italy and boasts one of the most layered urban histories in the Mediterranean. From its origins as a Spartan colony in Magna Graecia to its zenith as a powerful maritime republic and later as a seat of princely and imperial power, Taranto has been shaped by civilisations as diverse as the Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Normans, and Bourbons.

Its history is also a history of conflict and reinvention. Taranto allied with Pyrrhus against Rome, defied imperial rule, survived brutal sackings, and endured centuries of foreign domination. In more recent centuries, it evolved into a naval stronghold and industrial centre – home to Europe’s largest steelworks and one of Italy’s key military arsenals.

Today, the city’s historic heart – the Città Vecchia – is a living museum of its past: home to Romanesque cathedrals, Baroque façades, and Byzantine chapels. Yet it is also a city grappling with its 20th-century legacy of environmental challenges, economic shifts, and cultural reawakening. To understand Taranto is to encounter the many faces of southern Italy: resilient, multi-layered, and continually in dialogue with its own past.

At Delphi

At Delphi, on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, in the largest sanctuary of the classical world dedicated to Apollo – where the Pythia, enveloped by intoxicating vapours rising from the earth, delivered her prophecies seated upon a bronze tripod – the Tarantines were present with two votive offerings, the bases of which have been found. These were placed, despite the distance between them, along the Sacred Way.

According to Pausanias, these were two distinct monuments: the earlier depicting bronze horses and captive women, the latter comprising statues of foot soldiers and horsemen. The former was the work of Ageladas of Argos, created in the aftermath of the Tarantines’ victory over the Messapians at Carbina (modern-day Carovigno); the latter was sculpted by Onatas of Aegina and Calynthus, after a subsequent victory over the Peucetians who had been aided by the Iapygian king Opis. Remains and fragments of the dedicatory inscriptions of both votive offerings have survived. According to De Juliis’s reconstruction, the first offering predates the grave defeat suffered by the Tarantines in 473 BC, while the second dates to the years following.

Mythical Origins

The history of Taranto is steeped in mythology, much like that of many of our ancient cities. Its intimate bond with the sea no doubt inspired the legend of Taras, son of Poseidon, god of the sea, who, according to myth, arrived on the Ionian shores astride a dolphin, an emblem still associated with the city, some 4,000 years ago, drawn by the beauty of the landscape and the advantageous natural harbours.

Alongside the myth of the eponymous Taras – likely derived from the nearby River Tara and more directly linked to the history of Magna Graecia – there is also the legend of Phalanthos. Various versions are given by Antiochus of Syracuse and Ephorus, but all agree in portraying Phalanthos as the leader of the Parthenians who, after adverse events in their native Sparta and on the advice of the Delphic oracle, left their homeland in search of a new one, eventually landing on the shores of Taranto.

The founding of the city is generally dated to around 700 BC, roughly contemporaneous with the early years of its great rival, Rome. However, the earliest human settlements were located on the Scoglio del Tonno (in the commercial port area, which was completely cleared in the early 20th century to make way for the port), at Porto Saturo (a nearby coastal resort), and at Torre Castelluccia. These settlements date back to the mid-third millennium BC.

Greek colonisation, contrary to some traditions, was not peaceful. The Greek settlers had to overcome the resistance of the native populations—the Iapygians. Nonetheless, under Greek influence, Taranto became the wealthiest city in Southern Italy and extended its influence into Ionian Lucania, founding in 433 BC a new colony, Heraclea (modern Policoro).

At the start of the fifth century BC, the urban settlement was still confined to what is now the Old Town, where the acropolis was located. By the mid-century, however, thanks to expansion that transformed it into a true metropolis, it began to spread into the present-day Borgo district. The city was then enclosed by imposing defensive walls, which also surrounded its vast necropolis – covering parts of the current Borgo and much of the modern urban area. This is evidenced by the frequent discovery of burial sites whenever excavation occurs.

Taranto maintained strong ties of friendship with another major colony of Magna Graecia – Syracuse. This bond was forged during the Peloponnesian War, when in 416 BC, the fleet led by Gylippus, sent by Sparta to aid Selinus and Syracuse against the Athenian fleet assisting Segesta, found refuge in the port of Taranto.

The Golden Age of Taranto under Archytas, its military struggles, and the arrival of Pyrrhus.

The Taranto of Archytas

In the years that followed, Taranto rose to become one of the most important cities of its time. Its most prosperous era arguably coincided with the leadership of the philosopher and mathematician Archytas, born in Taranto around 428 BC. A follower of Pythagorean thought, Archytas was greatly admired by Plato himself.

It was during Archytas’ seven-year tenure as strategos (general) that Taranto – supported by Syracuse – extended its dominion across the Puglian territory. It also became a significant commercial hub, maintaining strong trading relationships with Greece and other Mediterranean lands. The city’s urban development reached impressive proportions, with some sources claiming its population reached 300,000 at its peak.

Diodorus Siculus, describing the city, claimed that Taranto was the most beautiful in all of Italy – surpassed only by Syracuse in Sicily. Its temples, curiae, double forum, splendid towers and other monuments were considered true works of art.

Thus, the Taranto of Archytas represented the pinnacle of its illustrious history – a city unbeaten in battle, though always vigilant of the threat posed by the Lucanians. However, as the years passed and that threat grew ever more pressing, the Tarantines – by then indulging more in luxury than in military affairs – were compelled to seek aid from Sparta.

Archidamus, King of Sparta and son of Agesilaus, answered their call for help. The Tarantines were engaged on two fronts: against the Lucanians and against the Messapians, their historic enemies. Yet the campaigns were far from victorious. After several lacklustre years, Archidamus was defeated and killed by the Messapians in 338 BC, allegedly beneath the walls of Manduria.

On the other front, the Lucanians overpowered the federated Greek forces, in which Taranto had a leading role, and succeeded in occupying Heraclea.

The Arrival of Pyrrhus

A brief reversal of fortunes came with another foreign ruler – Alexander the Molossian, son of Neoptolemus and King of Epirus – who, in pursuit of his own ambitions, managed to conquer Cosenza. But in 330 BC (approx.), he died in battle near Pandosia, close to Santa Maria d’Anglona, reportedly drowning in the River Sinni.

Thereafter, due to their dwindling military prowess, the Tarantines increasingly turned to external generals and mercenaries. These included Cleonymus, a Spartan prince who negotiated peace with the Lucanians, and Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse. In 317 BC, Agathocles was appointed strategos of Taranto with full powers and set out to forge an ambitious dominion stretching from the Ionian arc and much of Sicily (excluding Agrigento), to the inland territories of the Bruttians, Crete, and even parts of Carthaginian lands. However, upon his death in 289 BC, this fragile empire collapsed entirely.

From the early third century BC, tensions with Rome – until then largely indirect – began to intensify. Many cities of the old Italiote League, including Locri, Croton, and Thurii, had turned to Rome for protection against repeated Lucanian and Tarantine attacks.

Rome, pursuing its southern expansionist policy, had agreed by the Treaty of Cape Lacinia (303–302 BC) not to enter the Gulf of Taranto, which was considered under Tarantine control. Nevertheless, Rome deliberately breached this agreement by sending ships into Ionian waters. Taranto’s response was immediate: Roman triremes were sunk and the city of Thurii, where Rome had a garrison, was occupied.

Rome’s attempts at reconciliation proved futile. The Tarantines rejected their peace overtures and even insulted the Roman ambassadors—an act famously recorded as “The Outrage of Philonides,” who, according to Livy, urinated on the clothing of ambassador Lucius Postumius.

In 282 BC, surrounded by Roman incursions and fearing further isolation, the Tarantines sought the help of Pyrrhus, King of Epirus. Then 37 years old and a descendant of Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus – who had briefly ruled Macedonia – eagerly accepted. His own ambition was to claim the lands of the Italiotes and Sicily for himself.

Pyrrhus arrived in Taranto in 280 BC with an army that, though perhaps fewer than the exaggerated numbers cited by some sources, numbered around 25,000 men – less than the Tarantine force, which was famed for its exceptional cavalry – and 20 war elephants, a species then unknown to the Romans.

Pyrrhus’s campaign, Roman conquest, and the Second Punic War.

The Pyrrhic Wars and Roman Conquest

The clashes between Pyrrhus’ allied army and the Romans became the stuff of history and legend. At Heraclea, in July of that year (280 BC), Pyrrhus emerged victorious – despite heavy losses – thanks largely to the war elephants, which caused chaos among the Roman ranks.

In the spring of 279 BC, the two forces met again at Ausculum (modern-day Ascoli Satriano). The battle ended without a clear victor and came to be known as another “Pyrrhic victory” – a win so costly it scarcely counted as such.

During the winter months, peace negotiations were attempted. However, the Carthaginians, wary of any reconciliation, persuaded Rome to abandon the talks. In a display of mutual interest, they entered into a pact with Rome and resolved to launch a joint campaign in Sicily.

The Sicilians, meanwhile, appealed to Pyrrhus – son-in-law of Agathocles, the former tyrant of Syracuse and strategos of Taranto. In 278 BC, Pyrrhus mounted a campaign there, but it proved inconclusive. Two years later, in 276 BC, he returned to Taranto. By then, however, the political and military situation had changed dramatically. The Bruttians and Lucanians had been subdued by the Romans, and when Pyrrhus marched north through Apulia to the region of Samnium in 275 BC, he was confronted by the legions of Manius Curius Dentatus and Cornelius Lentulus. The Romans inflicted a crushing defeat.

Pyrrhus retreated to Taranto but, under the cover of night, fled back to Epirus. He died in 273 BC during battle against Greek forces led by Areus, King of Sparta.

With Pyrrhus gone and the Epirote garrison withdrawn, the way was clear for the Romans. They seized Taranto in 272 BC and incorporated it into their system as a federated city. The poet Leonidas chose exile rather than live under Roman rule, while the dramatist Livius Andronicus was taken to Rome as a youth, where he became one of the founding figures of Roman literary theatre.

The Second Punic War and the Sack of Taranto

Eight years later, the First Punic War erupted. Taranto maintained a neutral stance – or, perhaps more accurately, offered its fleet in service of Rome, which under the command of Gaius Duilius achieved a string of brilliant naval victories.

However, in 218 BC, as the young Hannibal set out to attack Rome by crossing the Alps, sentiment within Taranto began to shift. His stunning triumph at Cannae in 216 BC and Rome’s increasingly punitive actions – such as executing numerous Tarantine hostages – swayed local opinion towards Carthage.

In 213 BC, the Carthaginians captured Taranto, slaughtering the Roman garrison. Hannibal thus secured a vital southern port. But his later misfortunes were also visited upon the city.

In 209 BC, Taranto was besieged and sacked by Quintus Fabius Maximus, who looted its immense treasures – including monumental statues by Lysippos. Strabo considered one of these, a statue of Zeus that stood atop the acropolis, second only to the Colossus of Rhodes. Fabius brought 30,000 slaves back to Rome – Tarentines and Carthaginians alike.

Although Taranto had been devastated, it was restored largely through the efforts of Fabius Maximus. Over the following decades, Rome attempted to rehabilitate the city, recognising its strategic significance.

Yet Taranto increasingly came to be seen not as a great power but as a desirable retreat. The poet Horace remarked that he preferred the unheroic calm of Taranto to the grandeur of regal Rome. Even Pompey – Julius Caesar’s eventual rival – had a summer residence there. Ironically, Taranto failed to support him in the civil war of 46 BC.

Some believe that the fateful meeting between Julius Caesar and Cleopatra took place in Taranto, after she had arrived there with her vast fleet.

However, Taranto was no longer the metropolis of old. Its prominence steadily declined, and it gradually faded into the broader history of Southern Italy.

The early Christian period, fall of the Roman Empire, and Taranto’s fate under successive rulers including the Byzantines, Goths, Lombards, and Arabs.

Christian Beginnings and the Fall of the Roman Empire

According to tradition, it was the Apostle Peter himself – accompanied by his disciple Mark the Evangelist – who first brought the message of salvation to Taranto at the dawn of the Christian era. However, it is more historically plausible that Christianity became rooted here, as in much of Southern Italy, during the fourth century AD.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire brought turmoil to all former Roman territories. In 542, Rome was seized by the Goths under Totila, son of Vitiges. But just a decade later, in 552, Totila was defeated by the Byzantine general Narses, sent by Emperor Justinian. Taranto passed first into Greek, then Lombard hands, becoming part of the Duchy of Benevento.

In 663, however, the Byzantines under Emperor Constans II launched a campaign to reclaim their former territories. After his death, Romuald, Prince of Benevento, retook Taranto and sacked it in a brutal assault.

Arabs and Byzantines

Taranto’s history continued to mirror that of the wider Mezzogiorno. In 840, it fell into the hands of Arab forces from the Maghreb, who had already been raiding across the Mediterranean, striking terror into ports throughout the South. Despite the violence, the Arab occupation brought some beneficial influences, particularly in crafts and trade, and perhaps even helped restore a city that had been reduced to little more than a village.

In 881, the Byzantines reconquered Taranto, only for it to be plundered once again in 927 by Saracens, who deported part of its population to North Africa.

It was the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros II Phokas who initiated Taranto’s reconstruction towards the end of the first millennium. The commonly accepted date is 967. According to historical sources – and widely corroborated by archaeological evidence – he also expanded the area of the Old Town through artificial infill.

Nonetheless, Taranto continued to live under the constant threat of Saracen raids, even though it was never again occupied by them.

Norman Conquest and the Hohenstaufen

In 1086, the city was conquered by Bohemond, son of Robert Guiscard, and entered the orbit of Norman rule, eventually passing – as did the rest of Southern Italy – into the hands of the Swabians. The enlightened emperor Frederick II, who left a rich legacy across Puglia, is said to have stayed in Taranto around 1224. According to the historian De Vincentiis, this was the same year Saint Francis of Assisi is believed to have passed through the city on his return from the Crusades.

Traditionally, Frederick is credited with building the beautiful church of San Domenico Maggiore, though it was actually founded later, in 1302. What is certain is that during his reign, the Benedictines left Taranto, their mother house at Monte Cassino having been seized by the Swabians.

Saint Francis is also said to have founded the convent that bears his name in Taranto, as he did in other cities across Puglia.

Angevin and Aragonese rule, the creation and development of the Principality of Taranto, and the city’s trajectory under Spanish and Bourbon dominion.

The Angevin and Aragonese Periods

Following the Swabians, the Kingdom of Naples passed to the Angevins. The Guelf Charles of Anjou, with the support of Pope Urban IV, defeated Conradin. Philip I of Anjou received the investiture as Prince of Taranto – a title that would be passed on to his descendants.

Under Philip’s rule, Taranto experienced renewed development. Upon his death in 1332, the Principality passed to his son Louis, who became King of Naples and married Queen Joanna of Hungary. After Louis’s death, the Principality was inherited by his brother Robert, and later by Robert’s son, Philip II. It was from Philip II that the title passed to James del Balzo (son of Philip’s sister), after the tragic death of Joanna the Schismatic, who had attempted to block the succession.

This principality, however, was short-lived. James had just enough time to bequeath it to Louis of Anjou. From him, it passed to Raymond, the son of James’s sister Maria and Nicholas Orsini, Count of Nola.

Raimondello and the Orsini del Balzo Dynasty

The complex disputes between the Angevins and the Durazzeschi marked the closing years of the 14th century. For Taranto, this culminated in the townspeople proclaiming Raymond (Raimondello) as their prince. He had chosen to retain both his father’s and mother’s surnames: Orsini del Balzo.

Raimondello married Maria d’Enghien, Countess of Lecce, and with him, the history of Taranto became closely intertwined with that of Salento. His rule was astute and forward-thinking. He encouraged commerce and trade, and made Taranto the capital of a principality that stretched across almost all of Puglia, parts of Basilicata, and even into Campania.

A notable symbol of his reign was the tower that once dominated the fortified citadel, demolished at the end of the 19th century. The principality was later inherited by his son, Giovanni Antonio, who became the last Prince of Taranto. He was betrayed and killed by his own men in 1463. The Principality of Taranto was then absorbed into the Kingdom of Naples, losing its political autonomy.

Both father and son are buried in the grand basilica of Galatina, in the province of Lecce, dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria. It was commissioned by Raimondello after a pilgrimage to Mount Sinai in 1375. Their cenotaphs remain there today.

Fidelity to the Aragonese

After this, Taranto’s importance began to wane, though its strategic military role remained intact. Under Aragonese rule, this role was reinforced. Ferdinand I, who succeeded his illegitimate father, Alfonso (Ferrante), ordered the construction of a new castle replacing the now inadequate earlier structure. The aim was to defend against repeated Turkish raids, as well as the lingering Angevin threat via Charles VIII, who would later claim rights to territories once held by his lineage.

The reconstruction of the castle was completed in 1492, around twelve years after Alfonso of Calabria had cut through the isthmus that connected the Old Town to the mainland, turning it into an island for better defence. This work also followed the brutal suppression of the “Barons’ Conspiracy” of 1485, in which Taranto’s rightful heir Angilberto of Nardò had participated.

It was the feudal barons themselves who had invited Charles of Anjou to invade. When Charles VIII took Naples in 1494, almost without resistance, Taranto stood out as the only Puglian city to remain loyal to the Aragonese. Yet even it could not avoid falling into Angevin hands the following year. Their occupation was short-lived, as the Aragonese retook the kingdom in 1497.

The Aragonese rule officially ended in 1502 when, under the agreement between Ferdinand the Catholic of Spain and Louis XII of France, the Spanish general Gonzalo de Córdoba captured Taranto. The city sheltered the last descendant of the Angevin line, the twelve-year-old Ferdinand, Duke of Calabria.

From Ferdinand, the Kingdom passed to Joanna the Mad, and then to Charles V, King of Spain, Naples, and the Americas. His name in Taranto is associated with the restoration of the city’s aqueduct and the fountain built in 1543, which supplied the main square with water until 1861.

Taranto’s role in the Battle of Lepanto, its experience under Spanish and Bourbon rule, and the arrival of revolutionary movements.

The Battle of Lepanto and the Spanish Dominion

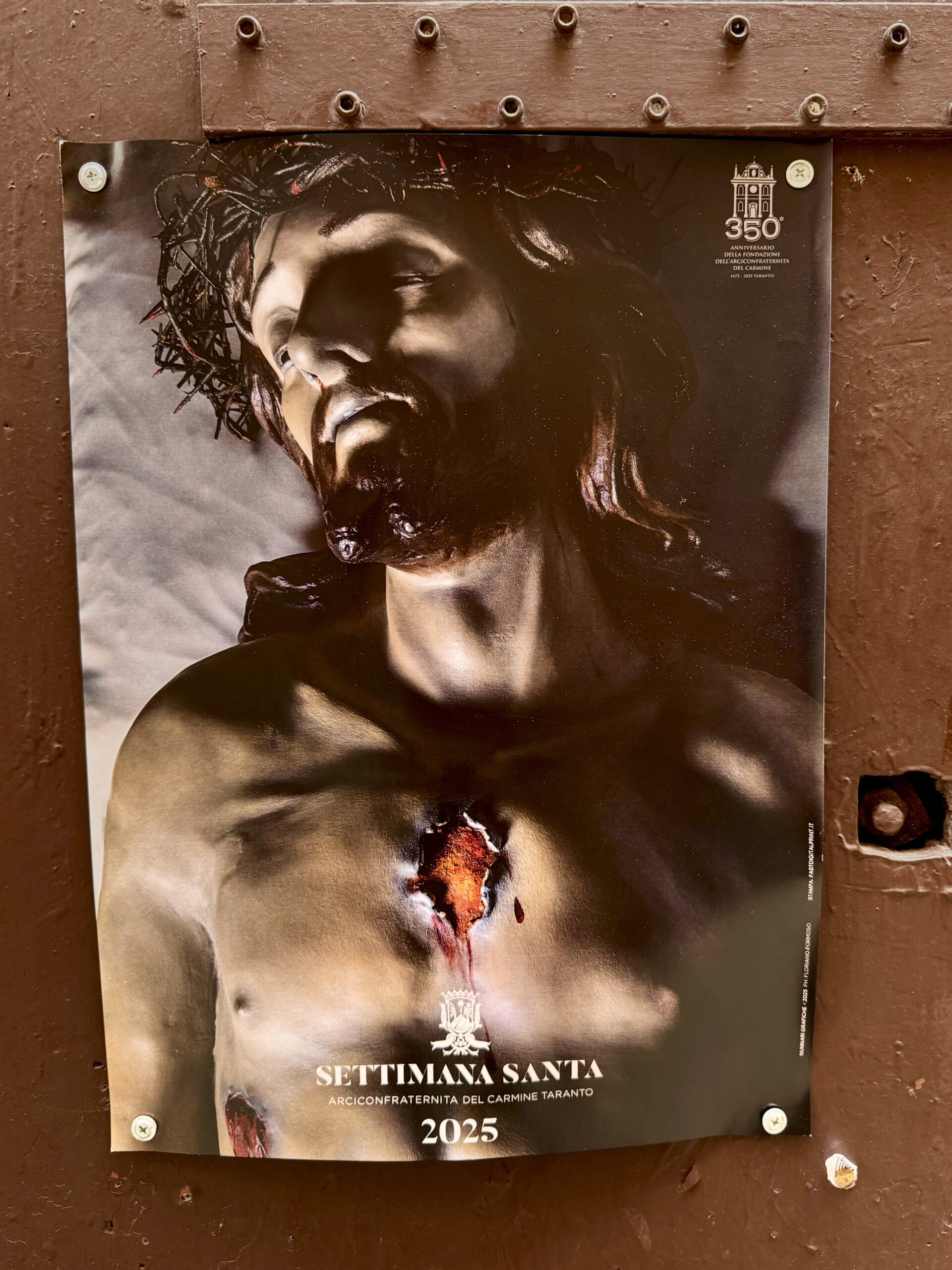

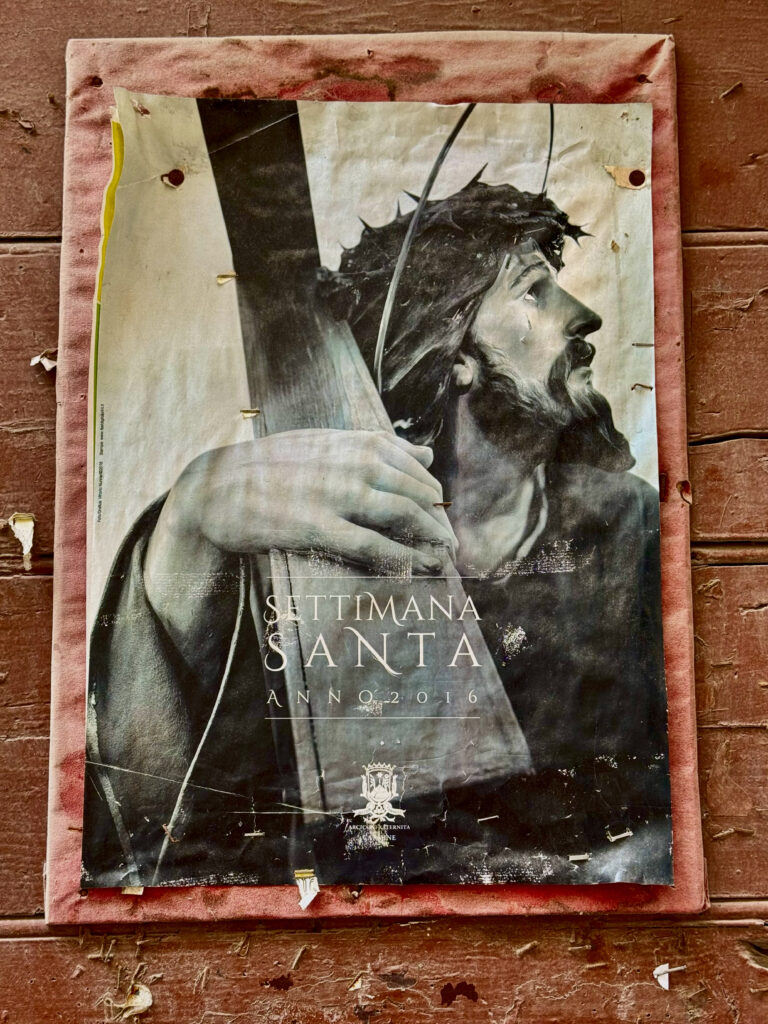

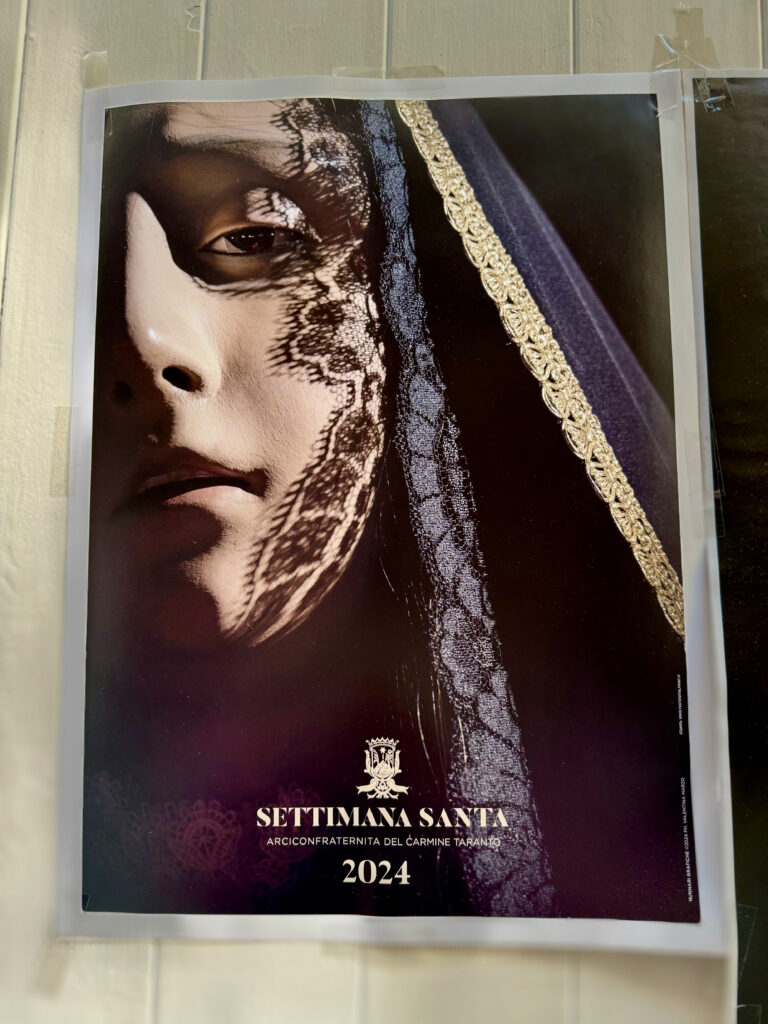

Taranto played a significant role in the Battle of Lepanto on 7 October 1571, a landmark victory for the Christian fleets summoned by Pope Pius V against the Ottoman Turks, who had resumed their threat to the region in the early 16th century. Along with the rest of southern Puglia, Taranto had been compelled to strengthen its coastal defences through the construction of watchtowers.

The city not only offered refuge to the Christian ships, particularly the fleet of Giannandrea Doria, but also contributed manpower to the effort. A few years later, the moat beneath the castle was expanded, rendering the city virtually impregnable to Turkish pirates. Despite these fortifications, in 1594 the Turks managed to destroy the abbeys of Santa Maria della Giustizia (on the edge of today’s Tamburi district) and San Vito del Pizzo at Capo San Vito.

Under Spanish rule, all of southern Italy was subjected to harsh economic conditions. In the 17th century, popular unrest flared throughout the Kingdom of Naples. In 1647, Masaniello famously led a revolt in Naples; the wave of rebellion reached other parts of the Kingdom, including Taranto, though there were no significant reprisals recorded locally.

The end of Spanish rule and the transition to Bourbon governance were met with a degree of hesitation, but were eventually accepted.

From Brother Egidio to Capecelatro: Taranto’s Enlightenment

In 1729, nine years before the arrival of Charles III of Bourbon, Taranto saw the birth of Egidio, a humble friar later beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1888 and canonised by Pope John Paul II on 2 June 1996.

A few decades earlier, in 1665, the city had given birth to Tommaso Niccolò d’Aquino, who died in 1724. He was Taranto’s greatest poet and the driving force behind the Accademia degli Audaci, best remembered for his Latin-language poem Deliciae Tarentinae.

Just two years into the Bourbon period, the composer Giovanni Paisiello was born. Universally celebrated for operatic works such as The Barber of Seville and La Serva Padrona, Paisiello received accolades at European courts.

Towards the century’s end, the revolutionary spirit unleashed by France reached Taranto. In January 1799, General Championnet proclaimed the short-lived Parthenopean Republic in Naples. Taranto followed suit a few days later. On 6 February, Mayor Michele Gennarini gathered citizens to elect the president of the new local government. Archbishop Monsignor Giuseppe Capecelatro was chosen, but he declined the role in favour of the nobleman Don Francesco Antonio Calò. On 8 February, a Tree of Liberty was erected in the city, just as it was across the rest of the Republic.

Capecelatro emerged as a pivotal figure in the city’s history. Erudite, witty, open to reform and skilled in diplomacy, he managed to prevent reprisals against pro-Bourbon factions, even though he himself wore the revolutionary cockade while defending the old regime. His nuanced position could not save him from prosecution. For having expressed favourable opinions toward the Republicans and General Championnet, he was tried and sentenced to ten years in prison, though he remained under house arrest until 1801.

He stayed in Naples to clear his name, but never returned to Taranto, which he continued to guide from afar until his resignation in 1817. Capecelatro gained a reputation as a Jansenist and served briefly as a minister under the rule of Joachim Murat.

Napoleonic Fortifications and the Return of the Bourbons

In April 1801, as a result of the agreement between Napoleon and Ferdinand IV, who was wary of British ambitions, French troops arrived in Puglia. General Soult was tasked with transforming Taranto into a strategic counterpoint to the British stronghold of Malta. He entered the city on 23 April with a well-armed force, seizing seventeen convents and monasteries to be used as barracks and fortifications.

Many of these structures and their armaments remained intact even after the Peace of Amiens, when tensions briefly eased and the French contingent withdrew.

Yet the peace was short-lived. By 1805, hostilities between France and Britain had resumed. The Kingdom of Naples was taken from Ferdinand and handed over first to Napoleon’s brother, Joseph Bonaparte, and then to his brother-in-law, Joachim Murat. Both leaders imposed new requisitions and defensive works. Murat, in particular, left a lasting mark on the city’s military structure and, in accordance with Napoleonic policy, founded Taranto’s municipal cemetery.

After the definitive defeat of the French and the Congress of Vienna, Ferdinand I of Bourbon returned to the throne. To suppress widespread brigandage in the Salento region, he turned to General Church, a British officer. Among the most infamous figures of the time was Ciro Annicchiarico of Grottaglie, known as “Papa Ciro,” a member of the secret society I Decisi and staunchly anti-Bourbon.

Taranto after Italian Unification, the rise of the naval and industrial complex, and the city’s transformation into a modern military and steel-producing hub.

After Italian Unification

In 1865, during the visit to Taranto by the princes Umberto and Amedeo of Savoy, the demolition of the city’s old defensive walls was finally authorised. This signalled the start of Taranto’s physical and urban expansion beyond the confined space of the old island, which had by then grown to accommodate nearly thirty thousand inhabitants.

Unfortunately, as in many other towns across the region, the uncontrolled and uncritical demolition works led to the loss of precious historical remains and irreparably altered the appearance of the historic centre.

At the same time, the idea began to take shape of endowing the city with productive infrastructure, albeit still with a military focus. In 1861, Cataldo Nitti, a former pupil of Capecelatro and future member of parliament, proposed the construction of a military arsenal. The Ministry of the Navy entrusted the project to Commander Simone Antonio Pecoret de Saint-Bon, who would himself later serve as Minister of the Navy (1873–76 and 1891–92). His name is firmly tied to the history of Taranto, as is that of French writer and general Pierre-Ambroise-François Choderlos de Laclos – author of Les Liaisons dangereuses – who was sent to Taranto by Napoleon and died there in 1803.

The law establishing the arsenal was not passed until 29 June 1882. It was backed by funding exceeding nine million lire.

On 22 May 1887, the revolving bridge (Ponte Girevole), a remarkable feat of engineering, was inaugurated. It allowed passage through the navigable canal, which had recently been widened and deepened (a project begun in 1883) to permit the transit of vessels destined for the naval base and arsenal. This intervention required the demolition of one of the castle’s bastions.

The military arsenal itself was officially opened on 21 August 1889 by King Umberto I, who visited the city accompanied by Prince Vittorio Emanuele and Prime Minister Francesco Crispi. In 1893, the first warship built in the Arsenal’s shipyards was launched: the Puglia.

Taranto as an Industrial and Military Hub

Taranto entered a new phase of expansion thanks to its enhanced military presence. While this development brought economic growth and job opportunities, it also meant that the local leadership made little effort to foster independent, civilian-led economic development.

This pattern would continue with the shipyards, established by the Gianfranco Tosi company from Legnano in 1914 and operational the following year. Over time, they produced numerous submarines and other vessels. However, after the Second World War, the shipyards gradually fell into decline. The last vessel to be built there, by then renamed the Taranto Shipyards and later absorbed into Fincantieri, was launched in 1959. Thereafter, the site was used primarily for repairs.

Taranto’s military and naval presence ensured it played a prominent role in every major conflict, from the war in Libya to both World Wars. During this period, an airbase was set up in Pizzone (later replaced by SARAM), the submarine Leonardo da Vinci was sunk in the Mar Piccolo, and the city suffered heavy bombing on 11 November 1940.

Post-War Decline and Industrial Expansion

The post-war recovery was slow and difficult. Like the rest of the Italian South, Taranto was plagued by unemployment. Many young people had no choice but to emigrate in search of work and a better future.

The city’s fate changed in the early 1960s, when construction began on the Fourth Steel Centre by the state-owned conglomerate IRI, now known as Ilva. Despite this, the city’s socio-economic structure did not fundamentally change. Even with the massive expansion of the steelworks, which became the largest in Europe and one of the biggest in the world, the same challenges persisted.

As global steel demand began to falter (a downturn predicted by some), Taranto found itself still completing the plant’s enlargement just as the crisis struck. A major protest movement emerged, remembered in history as the “Vertenza Taranto”, unifying political and social forces around demands for government support. This led to the construction of the molo polisettoriale, a multi-purpose commercial dock costing over 1,200 billion lire, intended to diversify the local economy.

Yet, nearly thirty years later, the issues remain unresolved. The steel plant was privatised, bringing severe social repercussions and sparking a major debate over environmental safety – a debate that continues to this day and is central to any discussion of the site’s future.

Environmental protection, always a long-standing concern, has gained fresh urgency following the arrest of company executives and former owners.

From horrible history to revival.

Troubled Taranto

The ILVA steelworks has a long history of environmental controversies. It has faced legal challenges related to the emission of pollutants and the management of hazardous waste and became the subject of a national scandal involving allegations of environmental crimes, corruption, and mismanagement.

The scandal began in 2012, when the Italian government seized control of the company and placed it under special administration due to concerns about the environmental impact of its operations. Subsequent investigations have revealed that the company allegedly engaged in illegal dumping of toxic waste and released high levels of pollutants into the air and water, leading to serious health problems for local residents. There have also been allegations of corruption within the company, including the use of false invoices to avoid paying taxes.

The ILVA scandal has received widespread media attention in Italy and has had significant political and economic consequences. The company has faced numerous legal challenges and has been the subject of ongoing efforts to clean up its operations and address the environmental damage it has caused. In May 2021 the plant’s former owners, Fabio and Nicola Riva, were handed lengthy prison sentences for their roles in allowing it to contaminate the city.

But its legacy reaches further. Studies have suggested that high cancer rates, especially among children, and other health problems are attributed to air pollution from elevated emissions of dioxin from the ILVA steelworks.

Production continues to this day and the steelworks still provide jobs for the people of Taranto.

Reviving the Heart of Taranto

For the better part of three decades, Taranto’s old town lay in near-total abandonment. Once the vibrant heart of the city, its winding streets and historic buildings were gradually emptied as residents moved away in search of better housing, spurred by the economic boom brought by heavy industry. As new jobs emerged, so did new aspirations – and with them, a preference for more modern, comfortable homes outside the ancient centre.

By the early 1990s, the population of the città vecchia had dwindled to a fraction of its former size. Most of the grand old buildings had become derelict shells, and large parts of the quarter stood silent. A significant portion of the real estate, then as now, remained in municipal hands, unused and unmaintained.

Now, however, change is underway. New regeneration projects aim to transform the old quarter into a living part of the city once more – vibrant, inhabited and open to the world. These efforts aren’t just cosmetic. Local leaders see the revival of the città vecchia as a catalyst for broader change. By unlocking the potential of Taranto’s cultural and historical assets, they hope to drive a new chapter of sustainable growth and pride in place.

It’s not just the old town getting attention. A striking €36 million redevelopment of the city’s Mar Grande waterfront is currently underway – a bold, contemporary gesture to complement the restoration of the past. The plan is to stitch Taranto’s three urban districts back together via an uninterrupted sea-level promenade, dotted with services, access points, and open spaces for public use. To reacquire and implement the relationship between the city and the sea. It will also link the city’s new cruise terminal with the base of the imposing Aragonese walls that ring the old city, offering arriving visitors a dramatic new vantage point on Taranto’s layered history.

Together, these efforts point towards a city determined not only to preserve its past, but to reimagine its future.

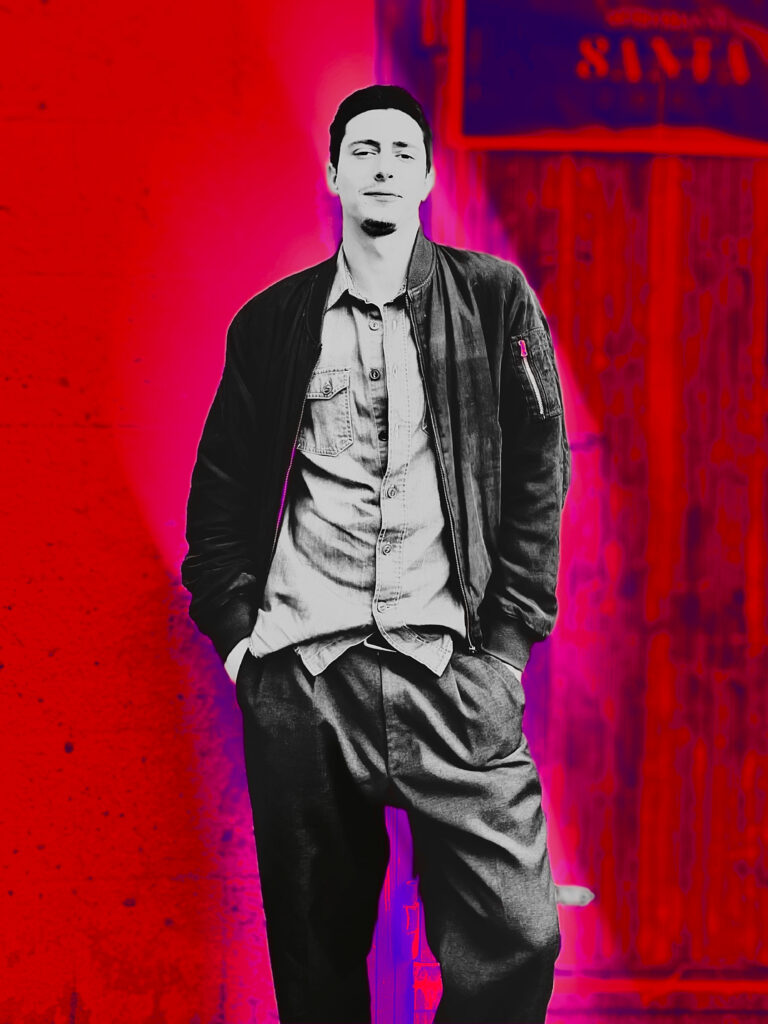

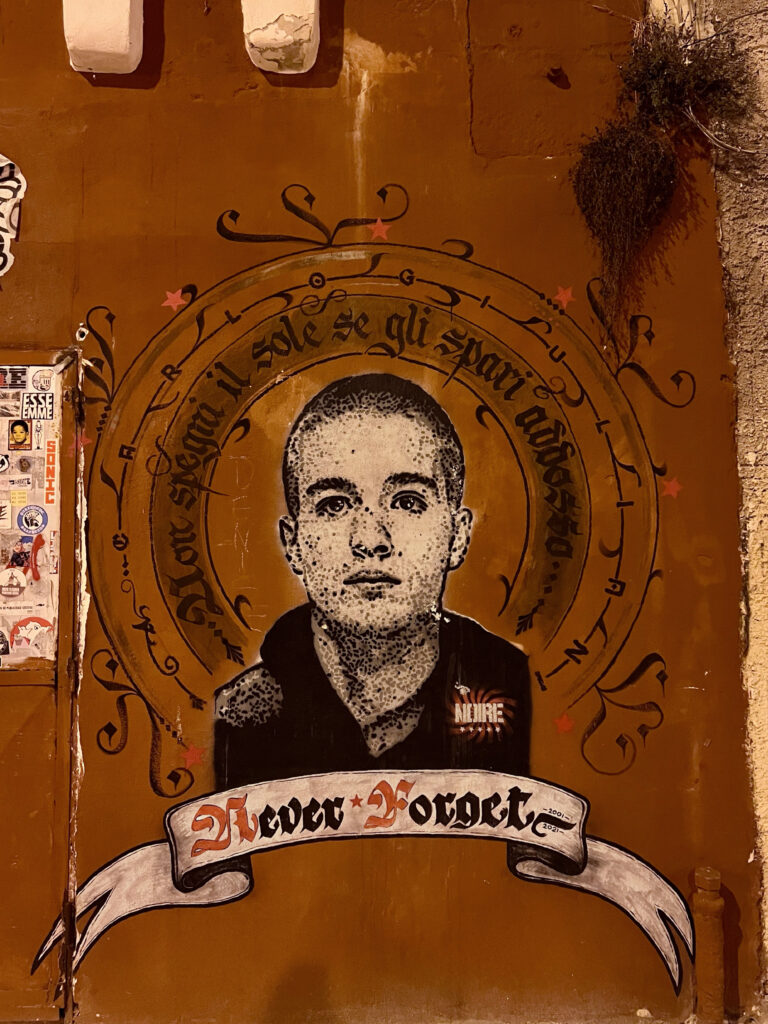

Within its winding alleyways new art galleries, wine bars and pop-up spaces are appearing alongside the street art and rusted street signs.

Culture is coming. A fuel that doesn’t pollute. And with it the slow gentrification that drags the old into the now. Taranto truly is a paradox, a city of contrasts.

Conclusion

Taranto’s story is one of endurance, complexity, and transformation. Few cities in Italy can claim such a rich tapestry of myth and memory, of artistic splendour and political struggle. From the Sacred Way at Delphi, where the Tarantines made their votive offerings to Apollo, to the steel furnaces that came to define its modern skyline, Taranto has always stood at a crossroads, between East and West, war and peace, collapse and renewal.

As the city looks to the future, it must reconcile its extraordinary heritage with pressing contemporary challenges. The scars of industrial overreach remain visible, yet so too does the enduring spirit of a community proud of its identity and ready to reclaim its place not only in history, but in the wider story of cultural regeneration in the Italian South.

For visitors, Taranto offers not just ruins and monuments, but a narrative of survival and reinvention. To walk its streets is to follow the arc of southern Italian history – from ancient prophecy to modern protest – and to glimpse a city that, despite it all, still rises.