What to See, Do and Eat in Gravina in Puglia: A Local’s Travel Guide

Gravina in Puglia (current population approx. 37,000) lies nestled in a valley on the Bradanic slope of the Alta Murgia, around 350 metres above sea level, approximately 50 kilometres from Bari and 20 km from Matera. The town stands dramatically on the edge of a deep and evocative ravine – known locally as a “gravina” – a typical geographical feature of many towns on the edge of the Murgia plateau. These steep, often erosive (and possibly tectonic) cuts in the limestone bedrock, dry except during heavy rains, are closely tied to the development of “rock civilisation” in the region (the constant water supply from the Gravina stream has encouraged human settlement here since ancient times).

Many visitors come to walk around the ravine. Otherwise during the day, apart from visiting the cathedral and the gravina itself, there was little else on offer (we visited at the end of May 2025), perhaps a symptom that Gravina in Puglia isn’t yet set up for tourism. We struggled to find a restaurant for lunch (thankfully we eventually did, one that boasted “we open for lunch”). Even for our late afternoon aperitivo the choice seemed limited. The old town had attractive moments, but it felt unloved elsewhere, if a little grubby. Modern structures stood aside old historic buildings, distracting from them.

However, by evening it had totally transformed and after dinner we found a vibrant old town centre with young people having fun.

Ancient Origins

Gravina is believed to be the successor of the Roman settlement of Silvium, mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana and the Itinerarium Antonini as a military and commercial station along the Appian Way. However, modern excavations by the British School at Rome at nearby Botromagno (or Pietramagna) hill have established that the area was inhabited as early as the 7th century BC. It is likely that Silvium was founded here by the Peucetians at the end of the 7th or beginning of the 6th century BC, as an inland outpost at the convergence of major trade routes linking the Adriatic, Ionian, Lucania and Daunia.

Involved in prolonged conflict with Lucanian and Messapian tribes, Silvium saw a resurgence during the campaigns of Alexander the Molossian (334–333 BC), as evidenced by bronze coinage depicting Zeus and Heracles. The town was later fortified by the Samnites before falling to the Romans in 306 BC after a fierce siege. Its strategic importance increased after the Social War, when Roman citizenship was extended to the population. In 83 BC, Sulla set up camp in Silvium during his march north from Brindisi.

Silvium thrived until at least the reign of Trajan, when the new Via Traiana, constructed as an Adriatic alternative to the Appian Way, drew trade and travel away. The town’s decline was hastened by barbarian invasions in the 5th century. Survivors took shelter in the tuff caves of the ravine, which were expanded from troglodyte dwellings into more structured habitation.

From Rock Settlement to Medieval City

By the 9th century, these communities moved back up to the ravine’s left bank, establishing what became known as the Civitas Gravinae. During the Byzantine period, following the Saracen capture of Bari in 841, Gravina was rapidly restructured and fortified. It became a bishopric in 867 and saw a period of wealth, as proven by gold coins minted under Theophilos (829–842). The town was thoroughly Greek in language, religious rites, and culture for over a century.

At the end of the 10th century, Gravina was besieged by the Saracens and then fell under Norman control in 1041–42. Granted as a fief to Humphrey and later Robert Guiscard, it became Latinised in both faith and administration. Construction began on the cathedral, perched over the ravine.

In 1231, Frederick II commissioned the Florentine architect Fuccio to construct a grand hunting lodge or falconry castle here. Substantial ruins remain today. Over the following centuries, Gravina passed through various feudal hands, most notably the Orsini family. In 1313, Robert of Anjou established an agricultural and livestock fair in the town—an event that became one of the largest in southern Italy and still survives.

Urban Structure and Population

Gravina expanded organically from its historic quarters – Fondovico, Civita, and Piaggio – into a maze of winding lanes and intimate piazzas shaped by religious, civic, and geological constraints. The medieval walls enclosed an area roughly bounded by the Vallone, municipal gardens, Piazza Scacchi, and Via Garibaldi – giving the town a distinctive “skull” shape.

Despite external pressures, Gravina maintained a remarkably stable population under the Orsini, ranging from 2,000 to 2,700 households between the 16th and 18th centuries. The family’s influence is seen in many churches and buildings, particularly those linked to Pier Francesco Orsini (Pope Benedict XIII).

A Walking Tour of Gravina

Piazza Cavour and San Domenico

Start in Piazza Cavour, overlooked by the Church of San Domenico (1675), featuring a Gothic turret and a four-faced public clock installed in 1892. In the garden stands the WWI monument by Leonardo Bistolfi.

Villa Comunale and Piazza Pellicciari

The municipal gardens lead to Piazza Pellicciari, home to the Church of Sant’Agostino, built by the Hermit Fathers in 1553. The trees running along the piazza are precisely structured and the piazza is unusually long and slender. During the afternoon we found all the bars and restaurants adjacent to be closed, though the piazza was busy by 8.30pm.

Chiesa Rupestre San Michele delle Grotte

Hidden within the caves of Gravina lies a remarkable rock-hewn sanctuary dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel. Originally a site of pagan worship, likely dedicated to Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, it was transformed into a Christian place of devotion by the 10th century. The sanctuary’s association with Saint Michael stems from the arrival of the Lombards, who liberated Gravina from the Saracen siege in 977, led by the emir Abu al-Quasim, an ally of the Byzantines.

The Lombards, who had already established Monte Sant’Angelo as a major shrine to Saint Michael in the 6th century, saw in the archangel a warrior protector – a fitting symbol for their people. Their devotion brought the cult of Saint Michael to Gravina, where it took firm root.

A Place of Pilgrimage

The earliest recorded description of the sanctuary appears in the 1574 pastoral visit of Monsignor Francesco Bossi. Even then, the feast day of 8 May, commemorating Saint Michael’s legendary apparition at Monte Sant’Angelo, was already being celebrated. During the episcopacy of Monsignor Cennini (1645–1684), Saint Michael was formally declared the patron saint and protector of Gravina.

Architecture and Devotional Spaces

The sanctuary of San Michele delle Grotte is carved into the natural rock and is accessed through a series of caves that serve as a vestibule. After passing the main gate and an initial cave, visitors enter an open courtyard and a corridor leading to a staircase – once connected to the ancient church of San Marco. Along this entrance corridor, pilgrims left behind graffiti and handprints, a touching sign of centuries-old devotion.

The sanctuary itself comprises five interconnected naves, separated by 14 pillars and ending in apses. Each apse holds a unique devotional feature:

- First nave (left): Frescoes from the 12th century depicting Christ Pantocrator flanked by Saint Paul and Saint Michael.

- Second nave: An altar with an image of Saint Gabriel.

- Central nave: The main altar, featuring a statue of Saint Michael carved in Gargano stone.

- Fourth nave: A statue of Saint Raphael.

- Fifth nave: Once home to an altar dedicated to the Guardian Angel, now relocated to the Cathedral’s sacristy in the late 18th century.

The statues of Saint Gabriel and Saint Raphael, both carved from local “tufino” stone, date to the early 18th century. Additional frescoes adorn the third nave’s right pillar, including a 16th-century Crucifixion scene featuring the Virgin Mary and Saint John.

Echoes of the Past

In a nearby cave, a haunting collection of human bones and skulls is on display. A plaque from the Fascist era attributes these remains to a massacre by Saracens during their third incursion in 999. While dramatic, this claim is likely symbolic – the bones were probably relocated here from multiple ossuaries across the town, including the crypt of the Cathedral (the Soccorpo).

Piazza Notar Domenico

Return via Calata Grotta San Michele to reach Piazza Notar Domenico:

- Public Fountain (1778, rebuilt 1858), fed by the Pozzo Pateo spring.

- Finya Library (1743): Founded by Cardinal F. A. Finya, it is Puglia’s oldest library, housing incunabula and rare 16th-century books.

- Church of Purgatory (or Santa Maria dei Morti): Now deconsecrated, built as a funerary chapel for the Orsini with a macabre portal and frescoes by Francesco Guarino. Completed by Angelo Solimena and possibly Francesco Solimena.

Cathedral and Piazza Benedetto XIII

In Piazza Benedetto XIII, pass the Seminary and Episcopal Palace, then reach the Cathedral. Built by the Normans and rebuilt after a 15th-century fire under Angela Castriota, it combines Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance elements. Inside are Baroque ceilings, 17th-century altars, and an impressive sense of spiritual grandeur.

The Cathedral of Gravina: Dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary

The Concattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta is an extraordinary space. Dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, it stands as one of the Gravina’s most significant and historic religious monuments. Its origins date back to 1092, when Count Umfrido d’Altavilla – of the noble Norman lineage of Robert Guiscard – commissioned its construction. According to the Cistercian abbot Ferdinando Ughelli, writing in the seventh volume of Italia Sacra (Venice, 1721), the Count appealed to Archbishop Arnaldo of Acerenza to restore Gravina’s episcopal authority, promising generous donations in support of the new diocese.

Romanesque in its origins, it blends Renaissance and Baroque features: Renaissance capitals, a Baroque ceiling, a 16th-century baptismal font, a 17th-century wooden crucifix, and an organ with 2,135 pipes. The Baroque altars are richly decorated with Neapolitan-style inlays in lapis lazuli, alabaster, mother-of-pearl and other precious materials. The 17th-century paintings reflect the influence of the Neapolitan school.

Romanesque Roots and Later Transformations

Originally built in the Romanesque style, the cathedral retains many of its medieval features both inside and out. A significant expansion took place in the 15th century, during which the west-facing façade was added – crowned by a magnificent rose window and a richly carved cornice adorned with floral motifs and symbolic apotropaic masks to ward off evil.

An Interior Rich in Symbolism and Craftsmanship

The cathedral’s interior follows a basilica plan and presents an arresting blend of styles. Its columns are topped by intricately sculpted capitals, each one unique. These support a series of elegant double-column mullioned windows that help lighten the structure.

Overhead, a gilded Baroque coffered ceiling frames five large canvases. At the centre is the most striking painting: The Assumption of the Virgin into Heaven, in honour of whom the cathedral is consecrated.

Treasures of the Right Aisle

The right nave houses several important artefacts:

- The baptismal font where Pope Benedict XIII – born Pier Francesco Orsini and perhaps Gravina’s most illustrious son – was baptised.

- A majestic statue of Saint Michael, attributed to the renowned Apulian sculptor Stefano da Putignano.

- A 15th-century stone altarpiece carved in Bitonto stone by local artist Guido da Guida.

- A wooden Christ figure, dating from the 16th or 17th century, which adds a moving spiritual presence.

Artistic and Historical Highlights of the Left Aisle

In the left nave, visitors will find:

- A 1779 painting by Bardellino, a Neapolitan artist, representing the rich artistic exchange between Puglia and Naples.

- A Byzantine fresco of the Madonna, a rare and evocative survival from an earlier devotional era.

- The Chapel of Bishop Arcasio Ricci di Pescia, built in 1632, where the bishop is buried beneath a stone monument topped by a bust now attributed to the celebrated sculptor Francesco Mochi.

- A 17th-century pipe organ, still in situ, which would have accompanied centuries of liturgical music.

- A stone relief of the Madonna of Constantinople, a devotional image held in great local reverence.

The Apse and Sacristy

The apse, crowned by a beautifully sculpted festooned arch, features a wooden choir stall dating from the late 1500s, constructed under the patronage of Bishop Manzolio. The sacristy, also reconstructed at Bishop Manzolio’s request, dates to the same period. Of particular note is the large walnut cabinet, made in 1561, which dominates the south wall – a remarkable example of ecclesiastical woodworking.

Via Matteotti and Via Cassese

From the Monastery of Santa Maria, walk down Via Matteotti to the Palazzo Orsini. Cross Piazza Buozzi to Via Cassese, reaching the Church of San Giovanni Evangelista (rebuilt in 1704), the former Palazzo Orsi (now Palazzo Capone Spalluti), and the Palazzo Pomarici Santomasi (17th c.), which houses archaeological finds, rural life exhibits, and the reconstructed rock church of San Vito Vecchio.

Santa Sofia and San Francesco

Along Via Clemente lies the Church of Santa Sofia, with the exquisite tomb of Angela Castriota (d. 1518). Nearby, San Francesco features a blend of Renaissance and Baroque styles, paintings by Sebastiano Pisano, and a notable organ and frescoes.

Madonna delle Grazie and the Ravine

Take Via Lettieri to the Church of Madonna delle Grazie, where the façade is shaped like an eagle embracing the rose window – emblem of Monsignor Giustiniani da Chio. Descend to the ravine via Via Fontana la Stella to visit cave churches like Santa Maria degli Angeli (7th–9th c.) and Madonna della Stella (13th c.), linked to the Benedictine Abbey of Banzi.

Pietramagna and San Sebastiano

From here, walk to Pietramagna Hill, where excavations have revealed 4th-century BC homes, tombs, mosaics, and imported ceramics. On Via San Sebastiano, visit the late Romanesque Church of San Sebastiano and former convent, with its severe cloister of pointed arches and cross-shaped pillars.

The Rock Churches and Bridge-Aqueduct

Built in the 18th century by the Orsini family, the bridge-aqueduct once supplied water to the Madonna della Stella sanctuary and the city. Today it links the two sides of the ravine and leads to the Botromagno hill and the Padre Eterno archaeological site. Near the bridge is the rock church of Santa Maria degli Angeli (also known as delle Tombe), with three naves, a central apse, faded frescoes, and altar.

At the base of Botromagno hill lies the rock sanctuary of the Madonna della Stella, once a pagan temple and later Christianised in 1550. It is named after a fresco of the Madonna and Child, the Virgin marked with a star on her forehead. Nearby is the Padre Eterno necropolis, while on the hillside above lies the Parco Archeologico di Botromagno, an open-air archaeological site covering over 400 hectares. Traces of settlement from the Iron Age are evident, when a large community spread across the ridge and ravine.

The Sette Camere and Later Sites

On the western side of the ravine stands the Sette Camere – seven interconnecting chambers carved into the rock during the early Middle Ages, spread across three levels. Visiting them involves hiking a narrow canyon path along the visually rewarding cliff edge.

The Sanctuary of the Madonna delle Grazie, just outside the town walls, was built in 1602 and features the coat of arms of Bishop Giustiniani, its patron, on the façade.

Finally, all that remains of Gravina’s Swabian Castle – one of the many fortresses commissioned by Frederick II across Puglia in the 13th century – are the perimeter walls and foundations. The silhouette of the ruined structure rising from the countryside makes for a dramatic sight, especially at sunset.

Gravina on the Big Screen: No Time To Die

Gravina in Puglia shot to international fame when it appeared in the 2021 James Bond film No Time To Die. Although it doubles for Matera, the film’s iconic opening sequence features Daniel Craig’s 007 sprinting across the Ponte Acquedotto – a breathtaking aqueduct bridge that spans Gravina’s deep ravine. With its dramatic backdrop of the old town clinging to the cliffs and views across the gorge, the bridge provided one of the most memorable moments in the film’s Italian scenes.

Since its cinematic debut, Gravina has welcomed a new wave of visitors eager to stand in Bond’s footsteps. The bridge is easily accessible on foot and makes for an excellent photo opportunity – especially at sunrise or sunset, when the golden light brings the ravine to life. Even outside its Hollywood moment, the bridge has long been a favourite local viewpoint, offering a striking perspective over the ancient cave dwellings and modern city alike.

The Cola Cola Whistle – A Sound of Local Tradition

Unique to Gravina in Puglia and the surrounding countryside near Matera, the Cola Cola is a traditional clay whistle with a single, droning note. Shaped like a stylised cockerel or hen, its name mimics the call of a bird once common in the woodlands of the Murgia plateau.

These whistles were originally crafted by local potters and ceramicists to celebrate the arrival of spring. In the past, they were also used in ceremonial contexts, and these days are often given to children as toys (you will hear them before you see them)!

Today, the tradition survives thanks to the Loglisci brothers who continue to handcraft these distinctive whistles, preserving a rare piece of local folk culture. To learn more, visit the Casa Museo della Cola Cola (Piazza Benedetto XIII, 24), where the history of the whistle and a colourful collection of examples are on display.

Where to Eat in Gravina

Gravina offers plenty of characterful spots to enjoy Murgian cuisine, from rustic trattorie to modern osterie. Here are some top picks:

1. Trattoria Mamma Mia

Website: trattoriamammamiagravina.it

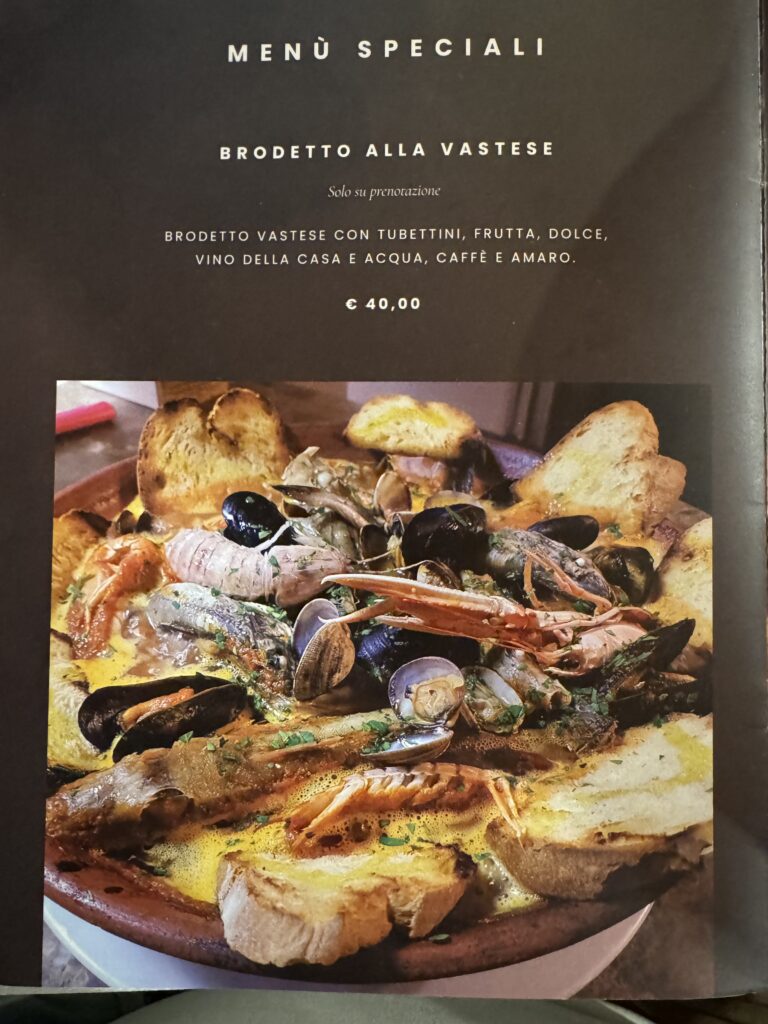

Recommended dishes: Brodetto alla vastese, gamberoni, grigliata mista di mare (huge seafood dishes), lamb cooked with wild herbs, local cheeses. A cosy, home-style eatery with seasonal specialities, generous portions and a great view over the gravina.

We love Trattoria Mamma Mia and have been recommending it since the first edition of our ’Best Restaurants in Puglia Guide’. If you think it sounds too much like the name of an Italian restaurant you would find in another country, then you’d be right. Owner Tommaso named it after a (now defunct) Italian restaurant he worked at in Glasgow in the late 1970s! For Glaswegian Italian restaurant aficionados he also worked at the well known The Spaghetti Factory and O Sole Mio!

Trattoria Mamma Mia has excellent food, generous portions and is incredible value. No need to buy an expensive wine, go with the house wine (10€ a bottle). We shared the antipasti tipici for two (between four of us), had one primo, three mains, four deserts, three coffees, two bottles of wine, two of water and four digestivi for 157€, which included the coperta cover charge of 2€ per person.

The antipasti included pane cotto (cooked bread), one of the most literal iterations of Puglia’s cucina povera tradition. Made from stale bread, nothing goes to waste, potatoes and in Gravina, cime di rapa. But do not be deceived. As unappetising as it may look, it is loaded with incredible flavour.

On Friday nights they do their legendary brodetto alla vastese (a fish stew/soup), but on other nights it is possible to have this – but only by ordering in advance.

2. Al Vecchio Crapo

Website: pizzeriaalvecchiocrapo.it

Great pizzeria with a fantastic outdoor terrace, and a modern and bright interior! Traditional dishes also available.

3. Trattoria Zia Rossa

Website: trattoriaziarosa.com

Typical Gravinesi dishes, makes this a good choice for fish and meat dishes. Delicious antipasti too. Stone setting with vaulted ceilings.

4. Arrosticiccio Braceria

A meatlover’s paradise.

Excellent braceria cooking a wide range of traditional meat and sausages over open grill. Tasty and delicious grigliata and bombette.

5. 13 Volte Luogo e Gusto

Website: ristorante13volte.it

Subterranean dining in a spectacular vaulted space across four levels, part of the historic centre’s old cistern system, extending 18m deep in parts.

6. Tracce

Specialising in fish and seafood, in a traditional setting.

7. Osteria La Murgiana

Website: lamurgiana.it

A beautiful setting gives the appearance of finer dining, but still at very reasonable prices. Typical dishes in a warm and inviting atmosphere, served generously. Some fixed menu choices.

8. Frugale

It’s only been opened for a few months serving up simple, but quality food. Limited and fixed menu choices, depending on seasonality and availability of produce.

Certainly — here is a revised version of the text in the style of the Puglia Guys travel guide:

The Balloune Festival – A Colourful Springtime Tradition

Every year on 8 May, the streets of Gravina’s Fondovico district come alive for the feast of San Michele delle Grotte. One of the town’s lesser-known traditions, the Festa dei Balloune turns the neighbourhood into a vibrant open-air display of colour, craft and community spirit.

The balloune themselves are handmade balloon-like lanterns, often described as miniature hot air balloons. They hang from balconies and doorways, swaying gently in the spring breeze. But it’s what’s beneath them that catches the eye: embroidered sheets, blankets, wedding dresses and finely woven fabrics – the traditional trousseaux once prepared for a young woman’s married life.

In the past, these displays served a purpose beyond decoration. They were a signal to visitors that a household had a daughter of marriageable age – and the festival was a rare chance to meet potential suitors. Families from nearby villages would come to Gravina, either to honour the saint or simply to take part in the celebration. Today, the custom lives on as a joyful expression of heritage and a visual reminder of how traditions once shaped everyday life.

Festa di San Michele Arcangelo

On 29 September, the town honours Saint Michael with a grand procession through the streets, accompanied by a brass band and costumed historical parade and musical events.

Getting there

Ferrovie Appulo Lucane (FAL) is a small regional rail company that connects Bari with the inland hills of Puglia and into Basilicata, with routes from Bari to Matera, Altamura, Gravina, Potenza, and Avigliano. Check the timetable (when due to travel you can also check in realtime) and buy tickets from the FAL website.

The main FAL station in Bari is just next to Bari Centrale, in Piazza Aldo Moro. The trains are reliable, efficient, and run from early morning until late evening.

The most popular route — and the one we get asked about most — is to Matera. The train usually splits at Altamura, with one half continuing to Matera Centrale (which is the stop you want) and the other heading toward Gravina. This means you may be asked to change at Altamura, but often it’s just a matter of being in the right carriage from the start.

Once you leave Bari’s suburbs, the line into Basilicata offers an atmospheric ride through the Murge hills — a dry, dramatic, and sparsely populated landscape that feels a world away from the coast.

Tickets can be bought from machines or staffed offices at the main stations, and also from bars and newsagents in smaller towns. There’s even a page on their site where you can check exactly where to buy a ticket at each stop — handy if you’re heading somewhere remote with no station facilities.

It’s a lovely way to see a different side of southern Italy — slower, more local, and very easy to fall in love with.

Alternatively you can reach Gravina in Puglia by car.

Gravina in Puglia is a city of extraordinary historical depth, where rock-cut sanctuaries, medieval streets, and Byzantine relics coexist. Its layered past, dramatic landscape, and hidden treasures reward visitors with an unforgettable journey through Southern Italy’s lesser-known heritage.