Galatina: Peter, Paul, Pizzica and Pasticciotti in the Heart of Salento

Tucked away in the sun-baked interior of southern Puglia, just a short drive from Lecce, lies Galatina – a city of elegant palazzi, storied courtyards, and one of Italy’s most important medieval churches. At first glance, Galatina might seem like just another sleepy Salento town, but its past tells a much more compelling story: of pirate invasions and Byzantine scholars, feudal dynasties and flourishing craft traditions. It’s a place where every stone has a tale, and every street corner reveals a chapter in a history stretching back over a thousand years.

From Pirate Raids to Fortified Walls

Originally, the Galatina settlement was located about two kilometres from where the town stands today. Repeated pirate incursions during the early medieval period forced its inhabitants inland and uphill to a more defensible site. By the second half of the 5th century, Galatina had enclosed itself within walls, a compact citadel of less than three hectares.

But the town didn’t stay small for long. After recovering quickly from a brutal Saracen raid in the 9th century, Galatina expanded its perimeter significantly. By the 970s, it covered around 15 hectares, reaching as far as what is now the western corner of Piazza San Pietro.

This was a crossroads period in more ways than one. Galatina found itself perched between the Byzantine “Grecia Salentina” (the still-visible Griko-speaking villages) and the Latin West. Here, Greek and Latin coexisted, not just in religious life but in daily conversation, until the late 1500s. This long Byzantine era was generally favourable: trade and culture flourished, and agriculture remained the town’s economic backbone, structured around Basilian monasteries and Italo-Greek spiritual centres.

Even today, traces of these Basilian hermitages can still be found scattered across the surrounding countryside.

A Town Shaped by Nobility and the Church

In 1335, under the patronage of the powerful del Balzo family, Galatina expanded again. The family left an indelible mark on the cityscape, constructing both a hospital and one of southern Italy’s greatest religious buildings: the Church of Santa Caterina d’Alessandria.

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, Galatina endured another tumultuous transition from the Kingdom of Aragon to Spanish rule. As regional tensions mounted, so too did the need for stronger defences. In 1539, the city completed its second ring of defensive walls, stretching over a mile and punctuated by five monumental gates, including Porta Santa Caterina and Porta Cappuccini. Sadly, little of this fortification survives today, but its legacy endures in the street names and city layout.

Galatina became a ducal city during Spanish rule, with the title of duke passing hands through inheritance and, frequently, through sale. By the time of the post-Napoleonic restoration, the Bourbon monarchy – short of funds – allowed well-connected noble families to divide the town’s feudal lands, stripping them from the monasteries that had held them for centuries. These religious orders, particularly the Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Benedictine-Olivetans, had not only shaped the spiritual life of Galatina, but had also fostered its intellectual and scientific traditions, especially in medicine and mathematics.

Meanwhile, the local economy boomed thanks to a thriving weekly market, regional fairs, and leather production tied to extensive livestock farming.

Strolling Through Stone and Time

The 18th century brought an era of grand transformation. Noble families constructed ornate palaces and elaborate churches, giving Galatina an architectural elegance that set it apart from neighbouring towns. It was also one of the few towns in Puglia where the streets were paved with solid stone.

Today, Galatina’s historic centre is a patchwork of Renaissance, Baroque, and 19th-century styles. Most buildings are two-storey, many with carved portals and handsome balconies. The interiors often use soft, friable tuff stone; façades are clad in local limestone or the golden Lecce stone that glows in the southern sun.

A unique feature of Galatina is its corti, or internal courtyards. There are 33 in total across the town. Originally designed for communal living, these courtyards usually feature a shared well, a stone washbasin, and often a single toilet. Around these spaces cluster the family homes. On the ground floor, rooms open front and back for air and light; upstairs, rooms are looser in layout and often lead onto terraces. While the façades may lack decorative flair, the corti offer a powerful glimpse into the communal life of working-class Galatinesi.

Over time, many of these courtyards evolved into elegant palazzi. One of the most striking is Palazzo Gorgoni-Nazzo on Via Cavour, its atrium a theatrical stage of arches and ornament, inspired by the classical 16th-century layout seen in nearby Corte Arcudi, located in the city’s oldest quarter.

Recommended Palazzi and Corti to Visit in Galatina

While strolling through Galatina’s elegant historic centre, don’t miss these standout examples of the town’s architectural heritage. From noble palaces to intimate shared courtyards, each reflects a different layer of Galatina’s story.

Notable Palazzi

- Palazzo Castriota Skanderberg

A noble residence linked to the legendary Albanian hero. Features a commanding façade and a fine example of late Renaissance architecture. - Palazzo Zimara–Arcudi–Calofilippi

A palatial complex with elements from multiple periods, offering insight into Galatina’s evolving architectural styles from the 16th to the 18th century. - Palazzo Bardoscia–Lubelli

Distinguished by its decorative balconies and refined courtyard. A symbol of Galatina’s baroque transformation. - Palazzo Mezio

A lesser-known gem with classical lines and a quiet, understated elegance. - Palazzo Tondi–Vignola

Located near the heart of the old town, this noble building impresses with its symmetry and ornate stonework. - Palazzo Arcudi

Representative of Galatina’s Renaissance court architecture, with a well-preserved inner courtyard. - Palazzo Coletta–De Mico

An elegant residence known for its finely carved entrance and noble proportions. - Palazzo Tafuri–Mongiò–Scrimieri

A magnificent baroque structure, notable for its decorative detailing and monumental scale. Now partly in private use. - Palazzo G. Galluccio

Formerly Palazzo Calofilippi, this elegant 18th-century palace dominates Piazza San Pietro with its refined lines and historical significance. - Palazzo Bardoscia

A key feature of Via San Francesco, known for its dramatic frontage and grand internal layout. - Palazzo Orsini – Sede Municipale

Once the seat of Galatina’s ruling Orsini family, this historic palace now serves as the town hall. - Palazzo Gorgoni del “Muto”

A striking and mysterious building with unique stone ornamentation and local legend surrounding its nickname (“of the mute”). - Palazzo Baldi

Located near Corte Baldi, this refined palace features a central courtyard and classic Salento detailing. - Palazzo Mongiò–Bardoscia

An architectural hybrid with Renaissance and baroque features, reflecting the joining of two prominent families. - Palazzo Gorgoni–Nuzzo

One of Galatina’s most scenographic residences, with a theatrical atrium and refined architectural flourishes—especially notable on Via Cavour.

Historic Corti

- Corte San Stefano

A classic example of a communal courtyard, with original stone washbasin and well still intact. - Corte Tripio

Quiet and atmospheric, this courtyard retains much of its 18th-century structure and communal layout. - Corte Santa Maria

Named after the nearby chapel, this courtyard is a well-preserved microcosm of Galatina’s shared domestic life. - Corte Cavour

One of the most elegant corti in town, framed by noble buildings and often included in guided architectural tours. - Corte del Fuoco

Now home to a popular pizzeria of the same name, this courtyard blends history with lively contemporary use. - Corte Baldi

Part of the old Palazzo Baldi complex, with a typical layout of multi-unit dwellings and a shared well at its heart. - Corte Vinella

A lesser-known courtyard with beautifully aged stone and strong visual character—an ideal photography spot.

A Museum Without Walls

Walking through Galatina today is like exploring an open-air museum. Via Cavour, Via Siciliani, and Via O. Scafo are lined with stately homes that reveal the wealth of Galatina’s merchant and noble classes during the 18th and 19th centuries. At the heart of the city is Piazza San Pietro, home to the imposing Palazzo Calofilippi (now Galluccio). From here, Corso Garibaldi leads past Palazzo Vernaleone, a fine Renaissance residence, and continues on to Piazza della Libertà, where Palazzo Tafuri (now Congedo) showcases high Baroque style.

Just a short walk away is Palazzo Bardoscia on Via San Francesco. Piazza Cavoti, in the old quarter, opens up like a stage in a Greek theatre, surrounded by layered perspectives and Renaissance façades that seem frozen in dramatic mid-scene.

Sacred Spaces: The Heart of Galatina

Religion played a profound role in shaping Galatina, and its many churches and chapels reflect both deep faith and a love of beauty.

At the spiritual heart is the Chiesa Madre (the Church of Saints Peter and Paul) begun in 1355 and completed in 1664. Classical in form and spatial arrangement, with baroque touches, its three vaulted naves are supported by clustered columns and lead to a richly decorated interior. Works by the Lecce-born sculptor Giuseppe Cino (17th–18th century) and paintings from the Neapolitan and Tuscan schools of the 17th and 18th centuries adorn the walls.

But the true masterpiece is the Church of Santa Caterina d’Alessandria, often called the most important religious monument in all of Terra d’Otranto. Built between 1384 and 1391 by Raimondello Orsini del Balzo and his wife Maria d’Enghien, the church boasts a Gothic façade with a stunning rose window and finely carved portal.

Step inside, and you’re met with five parallel naves separated by ambulatories – an extraordinary architectural choice in Puglia. The soaring central nave, inspired by Assisi’s San Francesco, is lined with intricate fresco cycles that reveal a blend of northern Gothic, Byzantine, and local styles. The octagonal choir, commissioned by Prince Giovanni Antonio Orsini, is bathed in light from tall windows and houses the prince’s elaborate 15th-century tomb.

Santa Caterina d’Alessandria in Galatina: History, Legend, and Architectural Mystery

In the 14th century, Galatina was still largely Greek-speaking, and religious ceremonies followed the Byzantine rite. However, a Latin-speaking minority struggled to understand the prayers. Raimondello Orsini del Balzo, the feudal lord of Galatina, sought to restore Latin liturgy to prominence, in keeping with his own culture and ambitions.

With the approval of Pope Urban VI, he commissioned the construction of the Church of Santa Caterina as a new centre of Latin worship. Alongside it, he built a hospital (today the Palazzo di Città) to offer free care to the poor and sick of Galatina and surrounding towns. He also founded an adjoining Franciscan convent, entrusting the friars with both the hospital chaplaincy and the responsibility of officiating in Latin within the church, as well as spreading Latin Christianity to neighbouring regions of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Initially, local Franciscan friars were considered for this task, but ultimately the Observant Friars Minor, active in the Bosnian missions, were chosen. This shift is documented in three key papal bulls: Piis votis and Sacrae vestrae, sent by Pope Urban VI to Raimondello and to the Provincial Minister of the Friars Minor respectively; and Pia vota, issued by Boniface IX to the Vicar of the Bosnian Observants.

A Question of Origins: Tradition vs Architecture

Although the traditional foundation date is between 1384 and 1391, architectural clues suggest a more complex story. The church’s five-aisled plan – unique in Puglia – features clustered columns, ribbed vaults, and pointed arches that blend Romanesque solidity with early Gothic refinement. Scholars have even proposed that parts of the structure, particularly the portico and pillars, may reuse or echo 13th-century Romanesque forms found in churches around Bari and Otranto.

The interior is a visual symphony. Nearly every surface is covered in frescoes, scenes from the Old and New Testaments, painted with astonishing detail and colour. Once mistakenly attributed to Giotto, the frescoes are now linked to the school of Francesco d’Arezzo, one of whose signatures appears dated 1432. Whatever their origin, the sheer scale and richness of the decoration rival those in Assisi.

Especially striking is the polygonal apse, a later addition commissioned by Giovanni Antonio Orsini and his wife Anna Colonna. Here, Gothic and Angevin influences take centre stage: tall, splayed windows, blind arcading, and a stepped pyramidal roof in the so-called modum Franciae style. The design even hints at Arab-Sicilian forms, brought to Puglia via Norman and Angevin courts, and reinterpreted with a restrained, early Renaissance classicism.

Even if you’re not religious, it’s hard not to be moved. This church is a testament to the faith, talent, and cultural layers of those who built and decorated it. For us, it’s the most beautiful we’ve seen in all of Puglia – and perhaps anywhere.

A Monument to Complexity

Today, Santa Caterina d’Alessandria stands as one of the most significant medieval churches in southern Italy, not only for its rich fresco cycle, rivalling even that of Assisi, but also for the complexity of its architectural narrative. It reflects overlapping layers of faith, language, and power: from Greek rite to Latin reform, from Romanesque solidity to Angevin elegance.

Whether one accepts the traditional date or embraces the Romanesque hypothesis, a visit to this Galatina landmark offers more than artistic splendour; it invites reflection on the fluid boundaries between East and West, myth and documentation, devotion and dynasty.

Pizzica, the Pulse of Galatina

To understand Galatina fully, you must hear it – not just in the sound of footsteps echoing through its stone courtyards, but in the wild, urgent rhythm of the pizzica. This centuries-old folk dance, once believed to have healing powers, is woven deep into the soul of the town.

Galatina is considered one of the spiritual homes of the pizzica tarantata, the hypnotic, trance-inducing form of pizzica associated with the ritual of exorcising women believed to have been bitten by the mythical tarantula. While versions of this tradition can be found across Salento, Galatina’s Church of San Paolo is at the heart of it.

History, Legend, and Tradition

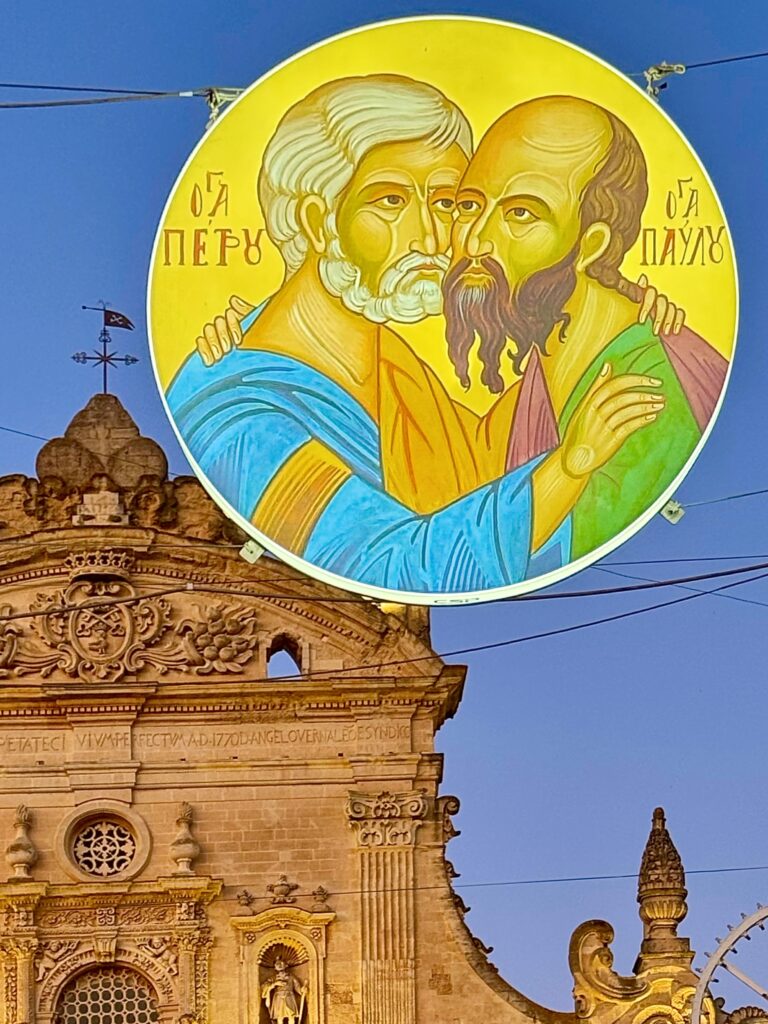

As in much of southern Italy, legend and history are deeply interwoven. According to tradition, Saints Peter and Paul stopped in Galatina during their journey to the Holy Land. The church named in their honour still preserves a stone said to have been the seat of Saint Paul.

Just a few steps away, inside Palazzo Tondi–Vignola, lies the Chapel of the Tarante, now consecrated to Saint Paul and long associated with the healing of women afflicted by tarantismo. In its courtyard stands a well, believed to have curative powers, a focal point for devotion that continues to draw pilgrims and the curious alike.

San Paolo and the Tarantate

Until the mid-20th century, each summer around the feast of Saints Peter and Paul (29 June), afflicted women – le tarantate – would make a pilgrimage to Galatina. Believing they had been spiritually or symbolically “bitten” by a spider, they danced feverishly to the rhythm of tambourines in hopes of healing. To be cured they came to drink from San Paolo’s well, and performed their rites in the shadow of the church.

The rituals combined pagan echoes with Catholic devotion, forming a unique blend of belief, music, movement, and myth. Though no longer practised in their original form, these traditions have left a deep cultural imprint.

La Festa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo (Saints Peter and Paul, 28-30 June)

Each year at the end of June, Galatina celebrates its patron saints. Music, faith, folklore, and food all play a central role. The town hosts religious processions, open-air concerts, and fireworks – but the highlight is the symbolic ballo delle tarantate, performed on 29 June in front of the Chapel of San Paolo.

The historic centre and main streets are transformed by elaborate luminarie, artistic light installations that bathe the town in colour and music.

In recent years, the streets are also festooned with zacareddhre (or zagarelle): colourful ribbons traditionally sold at patronal festivals. Once used in tarantismo rites, the ribbons were waved in front of the afflicted person to identify the disturbing colour, which was then torn and stamped upon as a symbolic act of release and healing.

The programme is rich with religious and folkloric moments. Especially moving is the procession of the saints, the solemn Masses, and the re-enactment of the tarantate ritual. Today this rite is performed by actors in traditional dress, who arrive on carts and dance in the piazzas to the hypnotic beat of tambourines and violins, evoking the wild rhythms of those once seeking healing through dance.

The evening of 28 June marks the Notte delle Ronde (the “Night of the Rounds”), an informal, collective celebration. After the processions, spontaneous groups gather in piazzas and alleyways, playing music and dancing pizzica until dawn. It’s a shared ritual, bringing together visitors and locals in a moment of deep connection and celebration.

The Ballo delle Tarantate

This ritual pizzica dance re-enacts the traditional healing ceremonies once performed for women believed to be suffering from tarantismo, a condition thought to be caused by the bite of a mythical spider. These “bitten” women (le tarantate) would dance frenetically to tambourines and violins, often for hours, in search of relief. The chapel was the spiritual centre of this rite, and its well was believed to hold healing properties.

Today, the ballo is a public celebration of cultural memory – deeply moving, fiercely rhythmic, and entirely unique to Galatina.

Today, the pizzica lives on in concerts, festivals, and spontaneous street performances. Galatina embraces its musical heritage with pride. During local festivals and summer celebrations, especially in late June, you can still hear the beat of tambourines in the air and witness dancers of all ages performing the steps passed down through generations.

For travellers, catching a live pizzica performance, whether in a piazza or during a sagra, is one of the most evocative experiences Salento has to offer. It’s not just music and dance; it’s a heartbeat, a living memory, and a celebration of community resilience.

Festival Highlights: Saints Peter and Paul in Galatina

The three-day celebration unfolds with a mix of sacred rituals, traditional music, and open-air festivities:

- 28 June – Festival Eve

The feast begins at 7pm with Holy Mass with a solemn procession of the saints an hour later. The lighting of the luminarie takes place at 9pm. Highlights for 2025 include a 50th anniversary concert by Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino, late-night folk music, and the evocative Notte delle Ronde, with spontaneous dancing in the streets until dawn. - 29 June – Feast Day

A full day of liturgical services culminates in the Rite of the Tarantate in Piazza San Pietro, a theatrical re-enactment of the traditional healing dance taking from 10.30am. Concerts fill the evening (starting late, from 10.30pm): in 2025 these include a Mina tribute concert, spiritual folk music by Talitakum, and a grand fireworks display at 1.30am. - 30 June – Day of Saint Paul

More religious observances and concerts close the festival, including a performance by the Giovanni Pascoli Youth Orchestra and a live show by Italian pop star Nek in Piazza Alighieri.

Festival Flavours

No Puglian festival is complete without food to celebrate the festivities. Throughout the festival market, you can taste local delicacies like:

- Copeta – a crunchy, almond-based torrone

- Lumache – seasonal snails, a popular street food

- Scapece Gallipolina – fried fish marinated in saffron vinegar

- Panini con salsiccia – grilled sausage sandwiches, an iconic festa favourite

Ciambottu

In Galatina, the feast of Saints Peter and Paul is traditionally accompanied by a hearty helping of ciambottu, a rustic vegetable stew that speaks of summer and simplicity.

Traditional Salento Ciambottu Recipe

Ingredients:

- 2 medium aubergines

- 2 courgettes

- 1 red and 1 yellow bell pepper

- 2–3 ripe tomatoes (or a handful of cherry tomatoes)

- 2–3 medium potatoes

- 1 onion

- 1–2 cloves of garlic

- Extra virgin olive oil

- A few basil leaves

- Salt and pepper to taste

Optional additions:

Some versions include beaten eggs stirred in at the end, or fish such as mackerel or anchovies for added richness.

Method:

- Chop all the vegetables into rough cubes.

- In a large pan, sauté the chopped onion and garlic in olive oil until soft.

- Add the potatoes first, allowing them to cook for 5–7 minutes.

- Then add the remaining vegetables, seasoning with salt and pepper.

- Stir, cover, and let simmer over low heat for about 40–50 minutes, stirring occasionally, until everything is soft and flavours have melded.

- Finish with fresh basil and a final drizzle of olive oil.

- Serve warm, at room temperature, or even chilled—ciambottu is delicious however you eat it.

Where to Eat in Galatina

Galatina may be better known for its baroque churches and as the birthplace of the pasticciotto than for fine dining, but it is quietly carving out a reputation as a culinary destination. From traditional trattorias to contemporary bistros, here are some of our favourite places to eat in Galatina:

1. Anima & Cuore

Via Liguria, 73

This cosy, modern trattoria brings a fresh perspective to classic Salento dishes. The menu is built around seasonal local ingredients, including ciceri e tria (fried and fresh pasta with chickpeas), and indulgent homemade desserts. Thoughtful and friendly service complete the experience.

Recommended for: A relaxed dinner with creative flair.

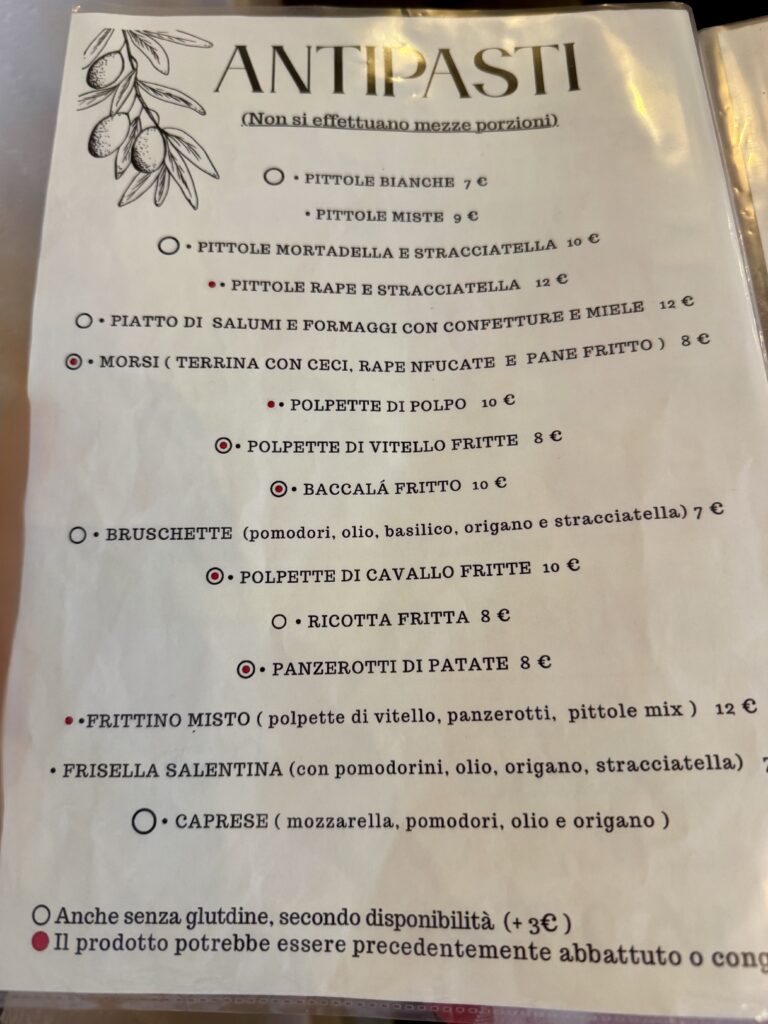

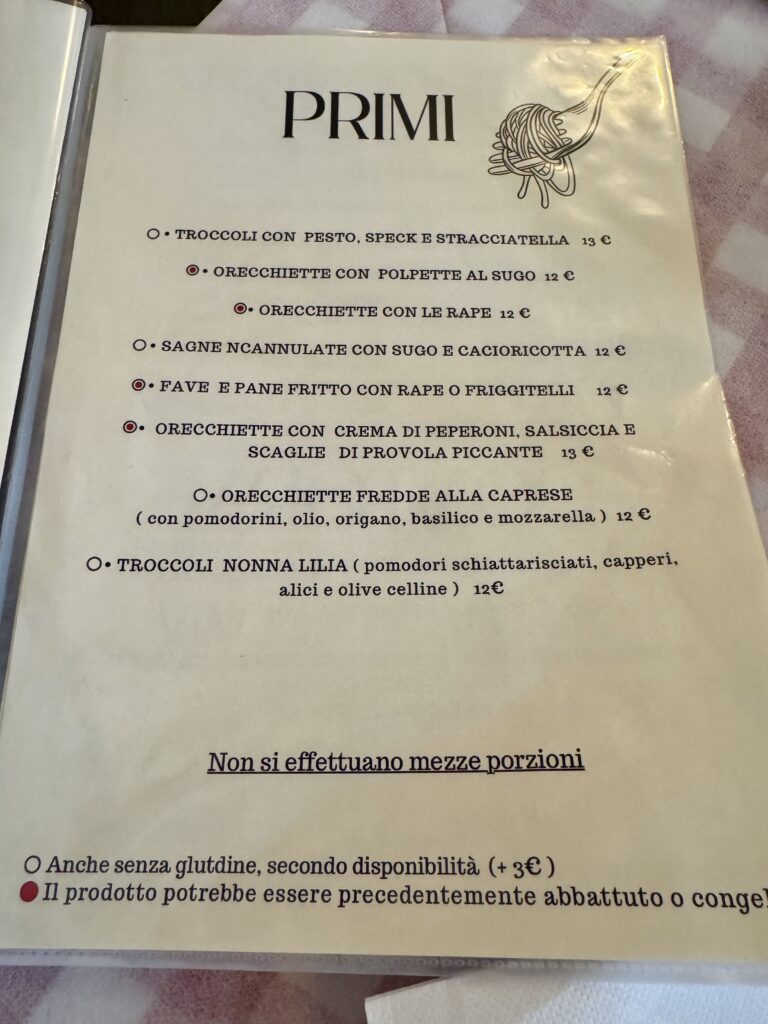

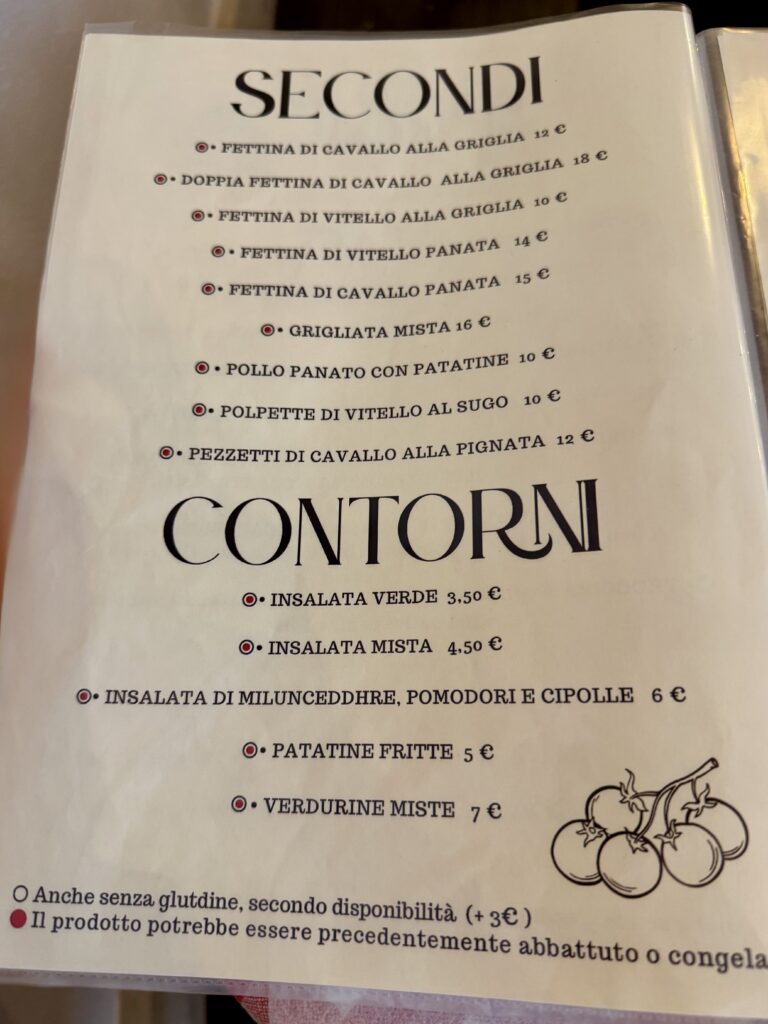

2. Nonna Lilia – Trattoria Tipica Salentina

Via del Balzo 9

Tucked away on a quiet side street just steps from the heart of Galatina’s historic centre, Nonna Lilia was filled with locals on our visit. This family-run trattoria champions the cucina povera traditions of the region with warmth, generosity, and an unpretentious flair.

Serving a feast of seasonal specialities, portions are generous and flavours are bold.

Recommended for: Typical Salento cuisine. Their pittole antipasti (fried dough balls) are legendary, and come in a variety of flavours, some served loaded with mortadella and stracciatella. The morsi (a Salento take on pancotto) made using chickpeas instead of potato blew us away.

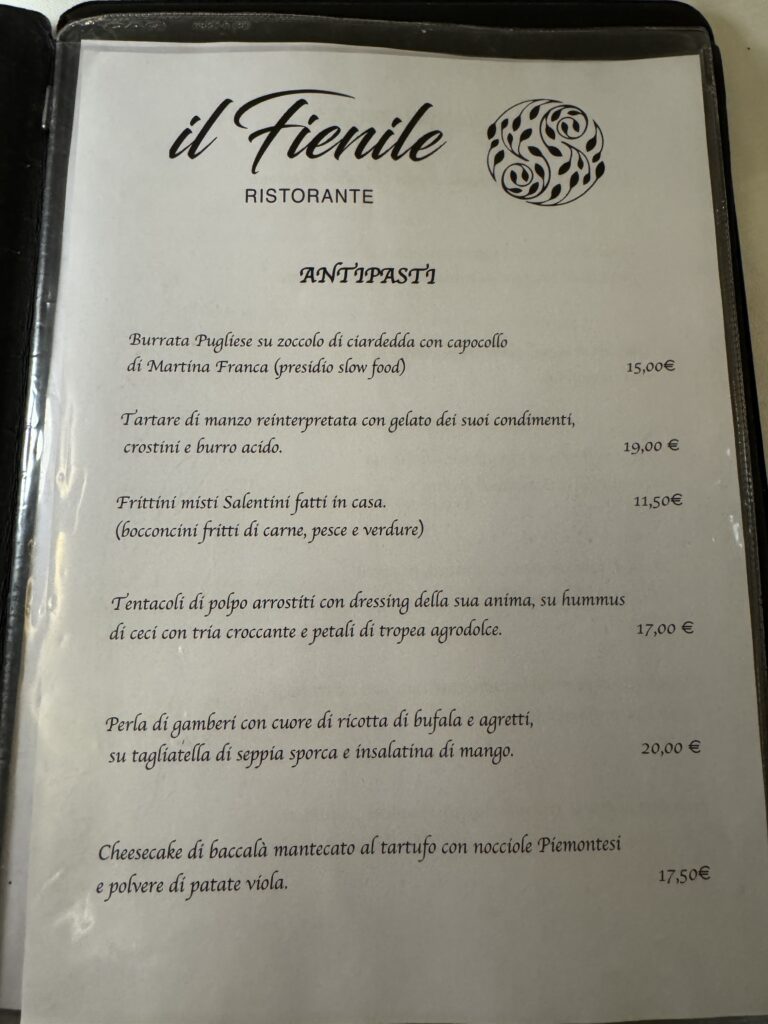

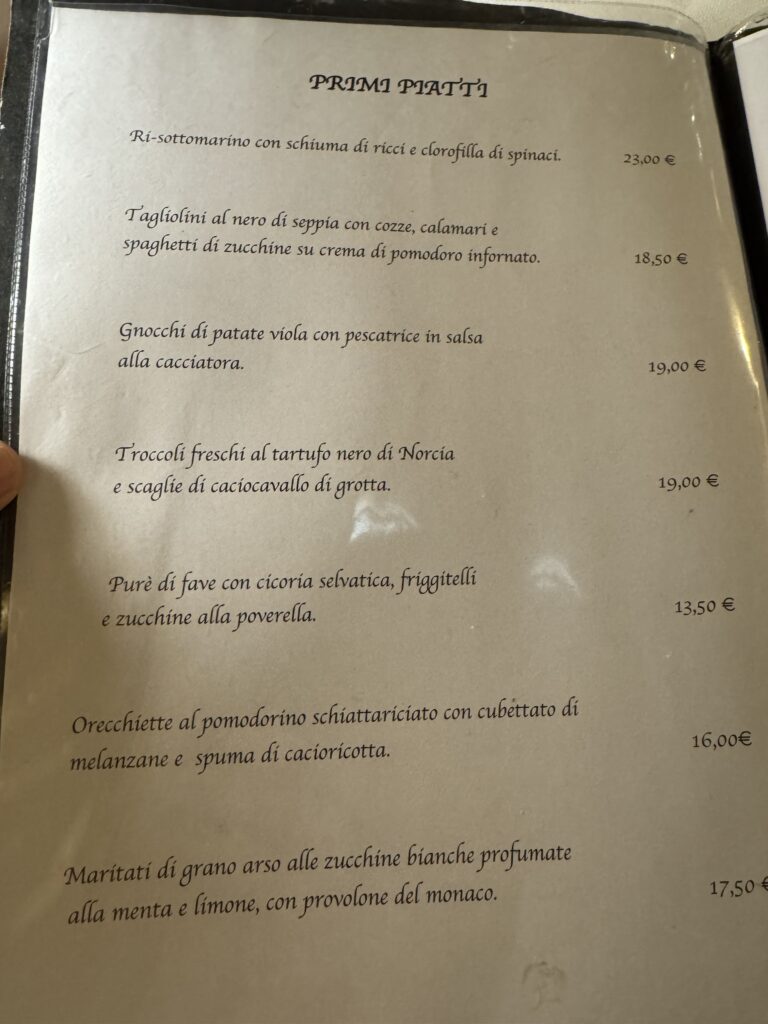

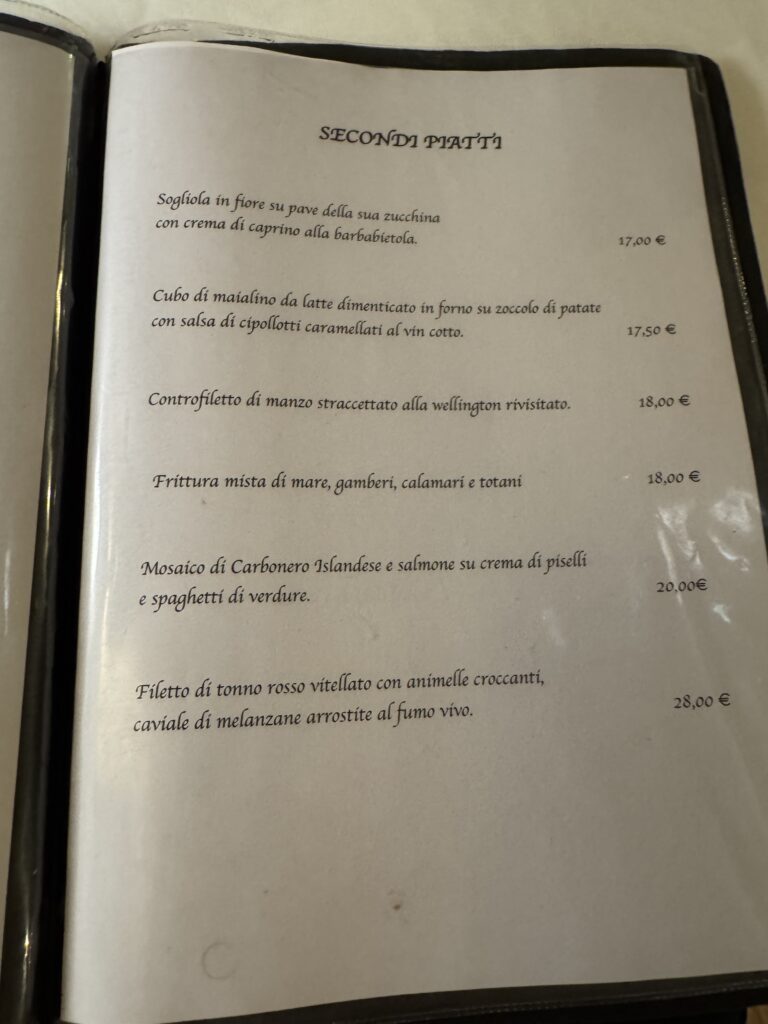

3. Il Fienile

Strada Provinciale 41, Galatina

Housed in a converted barn just outside town, Il Fienile is a rustic gem offering hearty local flavours with a refined touch. Favourites include grilled octopus and tagliata di manzo (sliced beef steak). In the warmer months, outdoor dining beneath the pergola adds to the charm. Towards finer dining, with some starters at 20€ and orecchiette maritate at 17,50€, but full of flavour and prepared with care. The home made bread rolls were perfect for the fantastic choice of Puglia olive oil, light and peppery.

Recommended for: A countryside lunch or dinner with traditional flavours. The pasticciotto ghiaccato was superb. A semifreddo of the custard filling with crumbled pastry on top and such delicious amaro cherries.

4. Pasticceria Ascalone | Staglio Panificati

Via Vittorio Emanuele II, 17 | 16

Legend has it that the pasticciotto leccese was born here in the 18th century (and many will tell you that Pasticceria Ascalone still makes the region’s best). This historic (but small) pastry shop, still run by the founding family, serves the iconic custard-filled pastry warm from the oven alongside other tempting sweet treats. Across the road, open from 8am until 10.30pm with a mid afternoon break is the equally fantastic baker, celebrated for its fantastic focaccia. Thick slabs of bread with a variety of toppings (including mortadella and pistacchio).

Recommended for: at the pasticceria. The shop is only open from 9am – 1.30pm and there is usually a queue (a line) of people. Focaccia from the baker (though they also have a great selection of pasties)

5. La Corte del Fuoco

Via Umberto I, 33

Located in the heart of Galatina’s old town, this lively pizzeria is beloved for its wood-fired pizzas, creative antipasti, and friendly, efficient service. With both indoor and outdoor seating, it’s ideal for a casual evening out with friends or family.

Recommended for: A laid-back night with excellent pizza and a local crowd.

Galatina rewards those who linger. It’s not just a city to visit, it’s a place to absorb. Whether you’re tracing the outlines of vanished city walls, admiring the noble elegance of its palazzi, or marvelling at the frescoed splendour of Santa Caterina, you’ll feel that timeless current of art, resilience and soul that still pulses through its stone streets.

One Comment